To acknowledge the 50th anniversary of the Strax affair, managing editor Cassidy Chisholm examines the period of unrest on the University of New Brunswick campus in 1968.

Graduate student Ken Moore was working as an Aitken House proctor in 1968 when he witnessed students causing a disturbance outside the biology building on the University of New Brunswick campus in Fredericton.

“I was coming out of Aitken House and I probably saw a lot of engineering students, sort of hollering and shouting outside the window, and it looked like it was getting out of hand,” Moore said.

This was just one of the altercations inspired by a period of unrest among students and faculty at UNB during the 1968-69 school year. Eggs would be thrown, protesters would march through campus hoisting signs above their heads, posters would be left on cars and by the end of it, there would even be a coffin-burning.

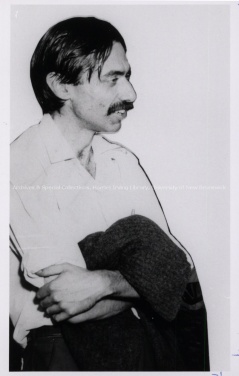

The source of this unrest was triggered by American UNB physics professor Norman Strax.

The Strax affair

Hired in 1966, Strax came to Fredericton after studying at Princeton and Harvard, bringing with him a passion for justice.

“[Strax] had been involved in student protests at the universities he had attended and he was very much against the war in Vietnam,” said Peter Kent, former executive assistant to UNB president Colin B. Mackay and author of Inventing Academic Freedom: The 1968 Strax Affair at the University of New Brunswick.

“He was shocked by the fact that Canadians students were not more concerned about war in Vietnam or many other things.”

However, Strax made an effort to change how Canadian students thought about the world around them. He encouraged students to fight for what they believed in and by February 1968, UNB students were holding a demonstration protesting the cost of student fees.

Their fervor was inspired and encouraged by Strax.

An opportunity to protest

In September 1968, UNB made student identification cards mandatory. Students had to show them when using the gym, when entering residences and when taking books out of the library.

Moore, who had worked in the library, recalls that Strax and some students thought ID cards were unnecessary.

“Norman Strax and some students had decided that to have to present a card to borrow books from the library was really a front to their freedom of speech and privacy, and although I agreed with their anti-war stance … I certainly didn’t see anything wrong with presenting an ID card to take out book. I didn’t think it was that big of a deal, but they did,” he said.

On Sept. 20, in a form of protest, Strax and his supporters went into the library stacks and retrieved armloads of books which they would ask to check out at the circulation desk.

“[The students] were told by the staff that they would have to present their ID card, and they chose not to do that, so they would leave those books there and go back and get another armload of books,” Moore said.

According to Kent, this “game” was called “Bookie-Book.”

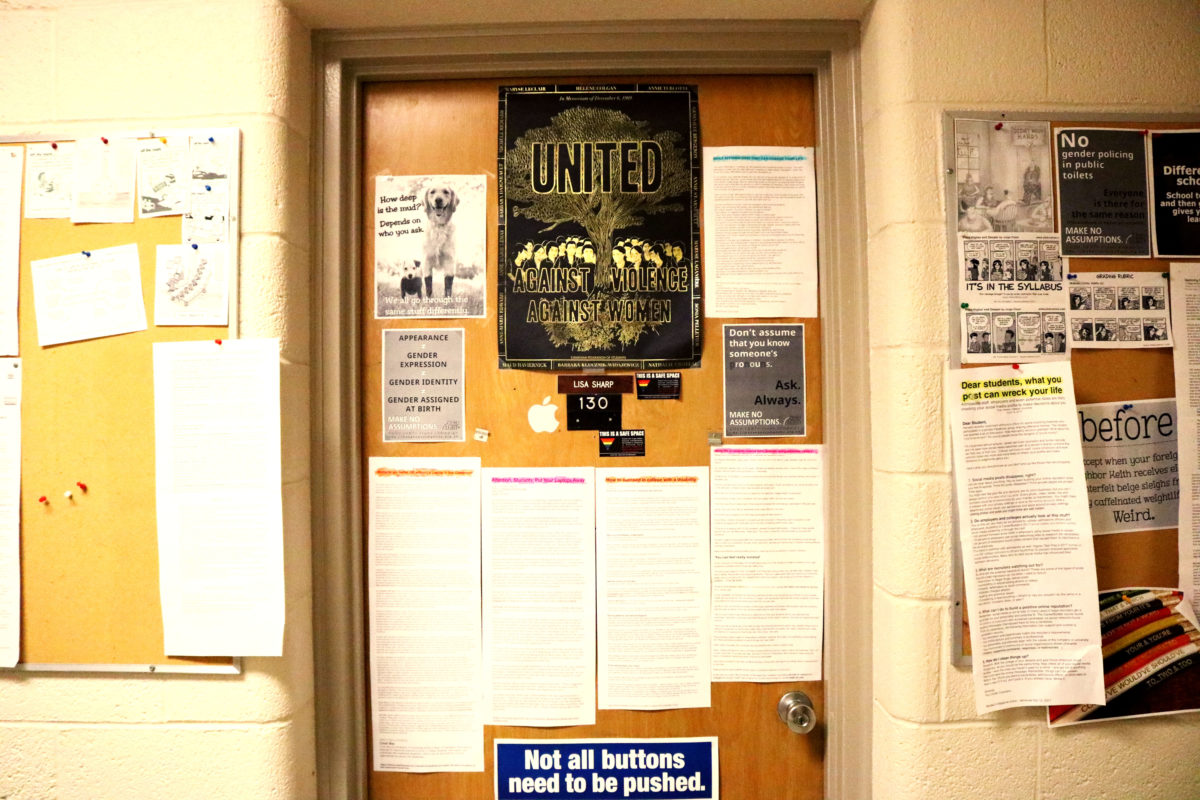

On Sept. 24, after three days of the “game,” President Mackay suspended Strax. He was asked to leave the campus, but instead, Strax fled to his office in Loring Bailey Hall, the biology building.

Strax and student activists occupied his office, room 130, for nearly two months, dubbing the space “Liberation 130.”

The coming months transformed the protest into something so much more. Did Colin B. Mackay have the right to treat a professor this way? The ID cards were forgotten and the real protest began.

A campus divided

Only the Board of Governors could fire Strax, but he was finally forced to leave the UNB campus when Mackay asked a judge to summon him to Saint John.

“Strax went to Saint John and … he had to leave the campus, then he was not allowed to come back,” Kent said.

“What had happened was, the president had used the courts against a faculty member so the issue of what Strax had done, was taken out of the hands of the university and put before the courts.”

According to Moore, the student activists who remained in Strax’s office faced significant backlash from other students, including students in engineering, forestry and business.

Windows were broken, garbage was tossed into the office and students attempted to forcibly remove the demonstrators.

This lasted until Nov. 10. Most students left campus for the holiday weekend, so the remaining students were removed by the Fredericton Police. However, the protest and discussion didn’t stop there.

A shift in the protest

After the demonstration in Liberation 130 cleared out, the Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT) took up Strax’s case. They disapproved of the reason why Strax was suspended, so they attempted to work with Mackay and the Board of Governors to create an arbitration committee to discuss Strax.

The Board of Governors refused to form a committee so CAUT officially censured the university on March 15, 1969, meaning professors from Canada, Britain and the U.S. were discouraged from teaching at UNB.

The censure nearly united the campus. Students were no longer pointing fingers at Strax because it was the Board of Governors that failed to diffuse the situation.

Strax remained the symbol of the dispute, however, he didn’t have much input after he was suspended.

On March 20, the student union organized a demonstration outside the meeting of the Board of Governors. The student body had built a makeshift coffin that represented the Board, which they carried through the snow to the building the meeting was being held in. Students wore black and lined up as if it were a funeral procession.

During that same meeting, the Board decided to set up an arbitration hearing for Strax, thus ending student involvement.

Although it was no longer about ID cards, Strax had gotten what he wanted. An opportunity for activism to inspire democratic justice.

The censure was removed on July 18, 1969. Strax never returned to UNB to teach, but his name was cleared.

In an article published in the Telegraph-Journal on March 21, 1969, Strax said, “We have demonstrated that we can defend ourselves. Our next step is to go on and really begin to fight and to kick out those who hold too much power … and to build a truly democratic society.”

Norman Strax returned to the United States to teach in Indiana and died in 2002 from prostate cancer.