By: Isaac Phan Nay, The Charlatan

OTTAWA (CUP) — It’s June 28, 2020, and Sarah Sharp is on the long strip of beaches near Sandy Hook, N.J., examining the carcass of a North Atlantic right whale calf. The calf is the son of North Atlantic right whale #3560, a female known as Snow Cone.

The day before, the U.S. coast guard towed the carcass to the beach, which sits about an hour’s drive south of Brooklyn. Now, Sharp, a marine mammal rescue veterinarian for the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW), stands on the sand trying to find out how it died.

Crews had already cut thousands of pounds of blubber off its carcass. Sharp inspects the calf for deep cuts, missing flippers and bone lesions—evidence the whale died entangled in fishing nets, which can amputate flippers and gash down to a whale’s bone under the constant tension and pressure of the ocean.

“It’s pretty amazing what the line can do to these guys,” Sharp says of fishing nets. “[It] can create really horrific and impressive lesions, and obviously be very painful for these whales.”

Instead, Sharp finds bone fractures and bruises on the calf, evidence it was struck by a boater. Vessel strikes are common for North Atlantic right whales, Sharp says, which tend to gather in crowded bays along North America’s east coast.

“It’s a tragedy, what’s going on on our planet right now in terms of extinctions, and the role human activities are playing in that,” Sharp says.

After years of whaling threatened the species’ abundance, Sharp says boat collisions and fishing nets keep pushing the North Atlantic right whale closer towards extinction.

The species is critically endangered. Per the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium’s latest estimate in October, the North Atlantic right whale population is just less than 340.

According to Sharp, the North Atlantic right whale is experiencing an “unusual mortality event,” dying at an abnormally high rate. Necropsies that determine how whales are dying, like Sharp’s examinations, give conservationists clues about what threatens the species.

Still, the majority of the species’ deaths go unspotted. Brian Sharp, the director of the IFAW’s marine mammal rescue and research program—and Sarah Sharp’s partner—estimates conservation teams only learn about a third of North Atlantic right whale deaths. But researchers across Canada are working to spot the whales from high above.

—

In his bedroom in Port Moody, B.C., Matus Hodul scans 200 square kilometres of the Atlantic Ocean near Cape Cod Bay for the craggy white tops of North Atlantic right whales.

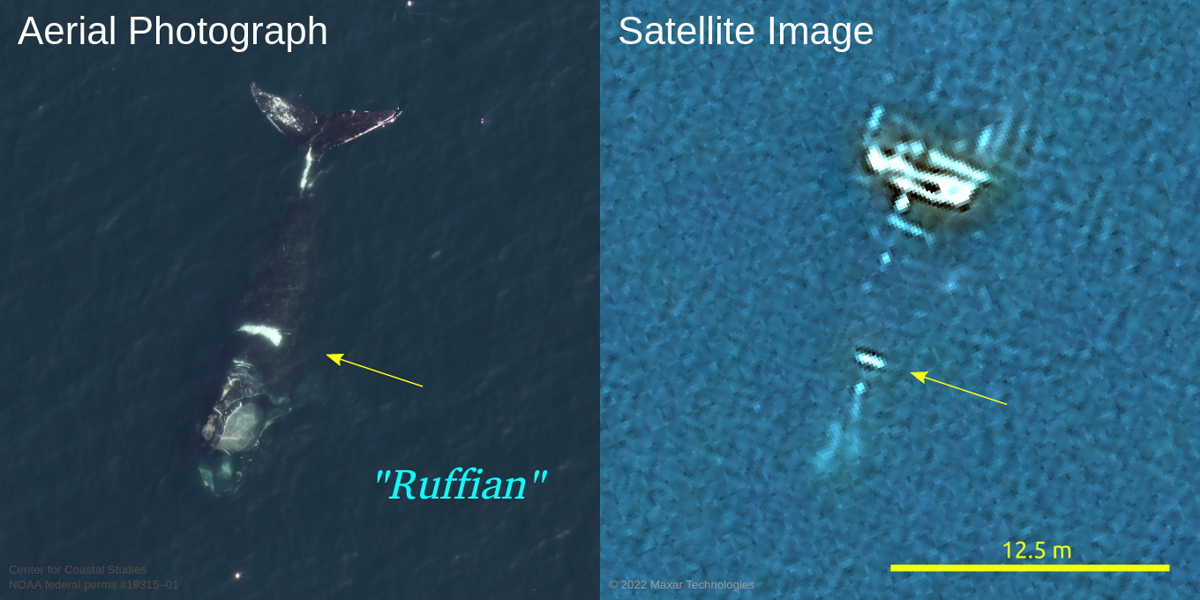

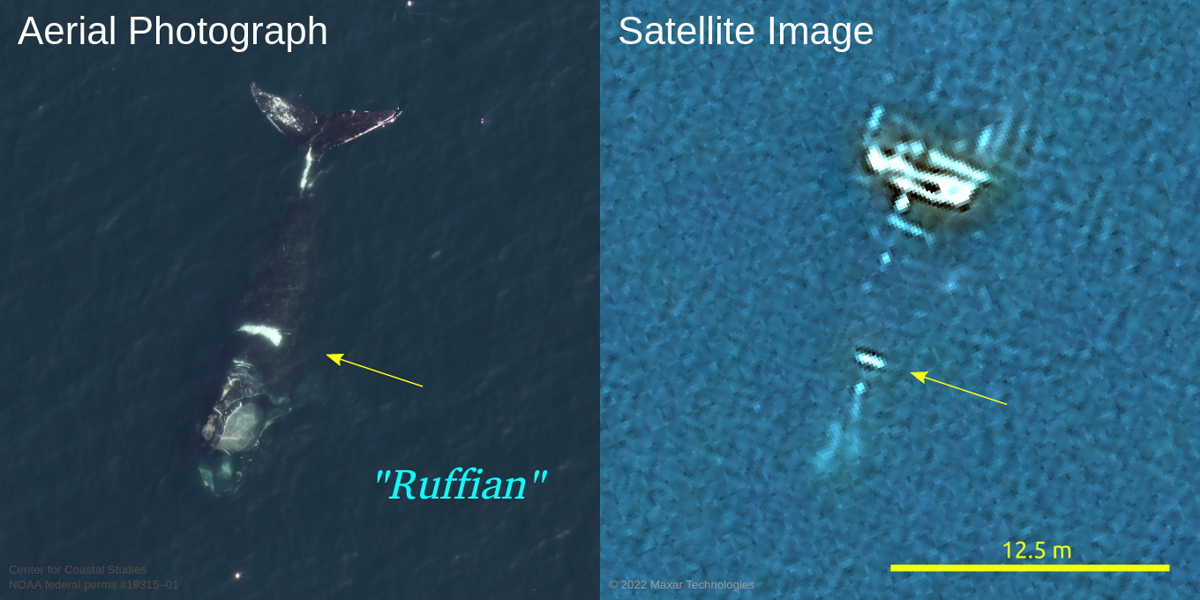

Hodul, a PhD candidate studying remote sensing at the University of Ottawa, had tasked a Maxar Worldview-3 satellite, equipped with 15-centimetre resolution, to take high-resolution photos above Cape Cod Bay at 11:40 a.m. ET the previous day. Now the next morning, April 25, 2021, the image arrives in Hodul’s email inbox.

Hodul’s team had also asked conservation group Center for Coastal Studies, which conducts aerial surveys of the whales, to take photos of the bay at the same time from airplanes above. By comparing them to the aerial photographs, Hodul can see if satellite imaging can spot North Atlantic right whales from orbit.

Being able to find the whales with satellite imaging, Hodul says, could be the key to preventing the collisions and entanglements that drive North Atlantic right whale deaths. But first, Hodul needs to find one.

Armed only with his computer mouse, Hodul frantically scrolls through the greyscale satellite image, though it only needs a couple more hours to process into full colour.

“I just wanted to see it right away,” Hodul says. He does not even know if spotting whales with the satellite is possible.

“The vast, vast, vast, vast, vast majority of it was just plain, boring blue water,” Hodul says. “So the majority of the time was spent just looking at blue water and saying, ‘Nope, there’s not a whale in there. Nope, there’s not a whale in there.”

Hodul does eventually find a North Atlantic right whale. He sends a screenshot of the mammal to his team. Ten minutes later, Hodul finds another. Minutes later, he finds a third.

By the end of the day, Hodul says, he has found 40 North Atlantic right whales in that image of Cape Cod Bay. Nobody had ever used satellite images to find North Atlantic right whales in Cape Cod before.

Hodul’s team published their research in the journal Marine Mammal Science on Sept. 1.

At the IFAW, Brian says the satellite imaging is a “much needed tool.”

“This might be our best option at being able to help figure out where whales go,” Brian says.

“Knowing where these animals are can give us the information that’s needed to be able to manage fishing and shipping around whale populations better.”

Researchers do not know where North Atlantic right whales go during the winter. Brian says without knowing where these whales go for half the year, conservationists can only protect these whales after they have been spotted.

In March 2021, researchers spotted Snow Cone entangled in fishing gear and managed to remove some of the rope. On Dec. 2, 2021, an aerial survey team for the Georgia Department of Natural Resources spotted a still-entangled Snow Cone with a newborn calf. By July, Sarah says, conservationists spotted Snow Cone without her calf, still trailing remnants of fishing line.

On Sept. 22, researchers at the New England Aquarium in Boston spotted Snow Cone from an airplane off the coast of Nantucket, Mass. The 22-year-old right whale was swimming southwards. Sarah says Snow Cone was entangled in a new set of weighted fishing gear—the fifth entanglement Snow Cone has endured.

Snow Cone has not been seen since. Sarah says she is waiting for another spotting, so teams can disentangle Snow Cone, but she is not hopeful.

“Whales are resilient. They’re amazing. They can always surprise us,” Sarah says. “But I would be shocked if she was able to come back from this, especially while she’s still trailing that really heavy gear.”

Normally, the IFAW relies on boaters to spot whales. The coast guard will often report when whales have been injured and respond to tips from a public hotline. Once a whale has been spotted, researchers can use acoustics technology to locate the animal or use airplanes to confirm a whale’s location.

Both methods are costly, Brian says. But each effort to reduce deaths could be the key to conserving the North Atlantic right whale population.

“When you only have just over 300 animals, every animal counts,” Brian says. “We can’t even lose one whale, or else the population can continue to decline.”

Even if a whale is spotted, efforts to save an entangled or injured animal may prove futile, Brian says, and “a lot of times, it’s too late.”

Hodul hopes satellites will be able to prevent such incidents before they happen. He says he wants to automate finding North Atlantic right whales within satellite imaging, so authorities can quickly spot whales from above and divert boaters and fishers.

Hodul has started work on part of this process. More than a year and a half after finding that first whale, Hodul says he just now is able to feed a satellite image into a program that spits out coordinates of where whales might be.

The program isn’t perfect, Hodul says. It often mistakes the white crests of waves for the white calloused ridges of a North Atlantic right whale’s head. Satellite images also miss whales that are deep underwater during the moment a picture is taken.

Still, Hodul and his team persist.

“Basically everything [humans] do is killing these whales, even if we don’t mean to,” Hodul says. “We’ve done this to them entirely. So it’s our responsibility to help them out, and find ways to stop killing them all.”

This article was shared via the CUP Wire, maintained by the Canadian University Press.