Assistant professor Mike Fleming teaches four to five courses per semester, spending an estimated 15 to 20 hours per week grading assignments — and it’s only a part-time gig.

Fleming is one of many professors trying to piece a career together at St. Thomas University.

Fleming is also a member of the Faculty Association of the University of St. Thomas, the union representing part-time and full-time academic staff.

“I manage to make a sustainable living, economically, by teaching the equivalent of three full-time jobs some years,” Fleming said.

“And doing it under unstable circumstances.”

The sociology and criminology professor’s situation is far from unique. Universities across Canada have been increasing the use of part-time faculty as enrolment numbers grow.

Fleming estimates a minimum of 15 people at STU in a similar situation to him.

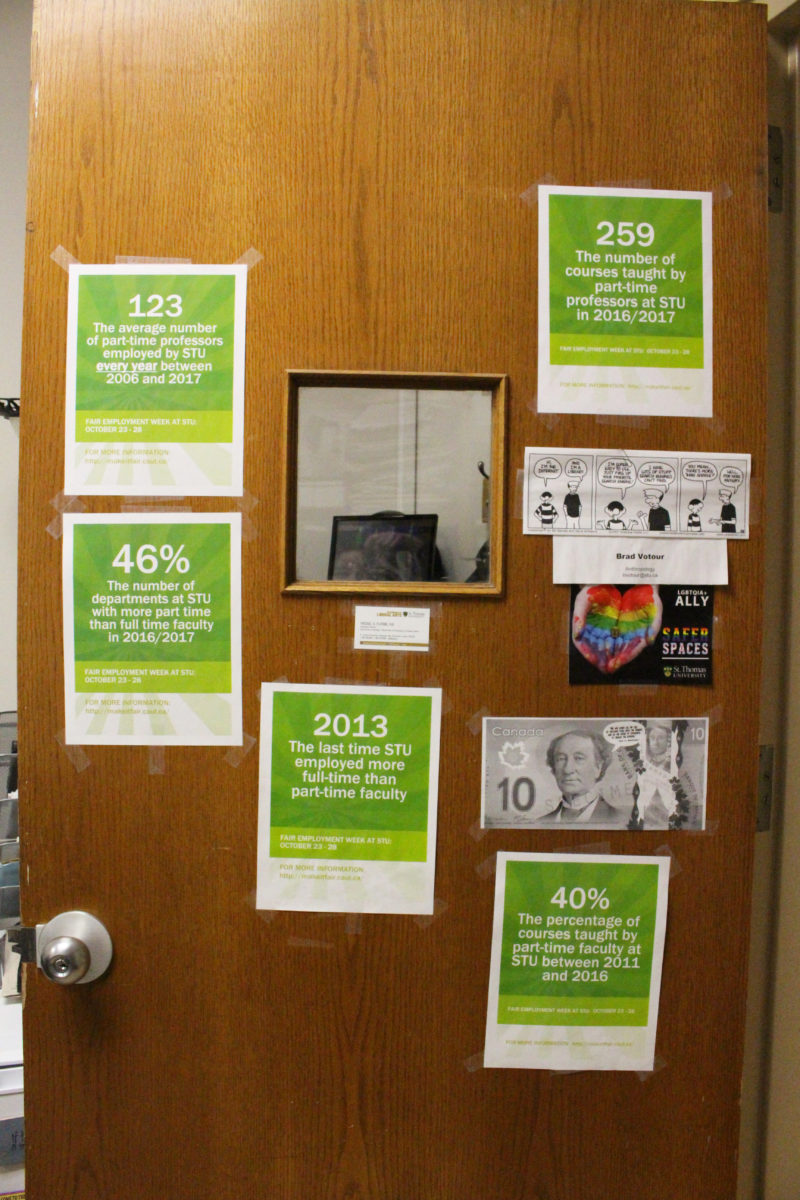

Between 2011 and 2017, 40 per cent of courses at STU were taught by part-time faculty. This year, data from FAUST and STU shows 46 per cent of departments have more part-time than full-time faculty.

Since 2006, only one academic year, 2012-13, saw the university employ more permanent full-time faculty than part-time.

By the numbers

But STU isn’t seeing the same spike in enrolment as other universities across Canada.

The number of full-time St. Thomas students is down 17 from last fall.

There is limited, incomplete data on part-time faculty in Canada. Ontario colleges report annually on the number of academic staff broken down by status, but public data only goes back to 2004. Most universities don’t report at all.

In that time, part-time faculty numbers have increased from 62.1 per cent to 67.5 per cent, meaning part-time instructors outnumber full-time faculty more than two-to-one.

The number of university students around the country has grown by 42.7 per cent since 1993, while the number of full-time faculty has grown only by 16.1 per cent, according to Statistics Canada.

Jeffrey Carleton, STU’s associate vice-president communications, said the purpose and duties of part-time and full-time faculty members are different, as written in the collective agreement.

Teaching and advising, research, scholarship, professional activities and service are the duties of a full time professor.

The collective agreement says the sole duty of a part-time professor is “teaching related responsibilities.”

Carleton said there’s a qualitative difference between why each are hired.

“If you ignore that difference, it looks like there’s an unequal treatment, but the fact of the matter is there’s an equal treatment, because the employment circumstances are entirely different,” he said.

Part-time staff also allow the university to deal with fluctuating numbers of full-time professors. Out of STU’s 103 staff, there are 13 faculty members on sabbatical and eight on leave this year.

Part-time deal

Part-time university professors trying to make a career in academia often work more hours than their full-time colleagues, without any of the benefits.

The latest collective agreement shows full-time salaries at STU for this year range from $60,333 to $81,957 for a lecturer, and up to $113,080 to $156,863 for a professor.

Part-time professors get $5,884 to $6,511 per three credit hour course. That means a part-time professor teaching five courses, the typical load of a full-time faculty member, would make between $29,420 and $32,555 — almost half of what the lowest-paid lecturer would make annually.

They also don’t receive health insurance benefits. Although, a health-spending allowance of $120 is available for each three credit-hour course taught.

Part-time professors are given a $50 stipend for supplies. Fleming said a lot of part-timers buy materials out of their pocket.

“If I need three binders for something, I’m going to buy it,” Fleming said.

“I may or may not think to submit the receipt.”

However, part-time professors can apply for part of an annual $10,000 research fund and receive pension contributions, a rarity in Canada.

Part-time professors can’t attend conferences, which typically take place in the spring, because they are teaching courses during intersession. There is also often out-of-pocket costs involved.

For full-time faculty, the university offers a professional development reimbursement fund of $35,000 annually for travel expenses related to scholarly work, research and study.

Dennis Cochrane, a part-time professor and 2010-11 interim president, recalled a few part-timers from his time as president who now have full-time positions. He described it as a way to break into the profession.

“It’s a process for people to get exposed to the university, and more and more the university can be exposed to them,” he said.

Carleton said decisions on full-time and part-time staff are made on a case-by-case basis. Factors such as overall student enrolment and enrolment within a particular program are considered.

STU is currently offering retirement incentives to full-time professors.

“It’s an economic reality with universities today,” Carleton said.

“At St. Thomas University, we’ve been very open in talking about our realigning of the number of full-time faculty positions with our current enrolment.”

Working condition challenges

This year for fair employment week, an initiative created by the Canadian Association of University teachers, FAUST put up posters to inform students of these faculty trends.

Fleming said he believes the nature of contract instructors shapes their ability to interact with students.

“Many of us are trying to do the same work as our full-time colleagues so anything that creates that kind of barrier between us and students is often something that students aren’t fully aware of,” he said.

Until recently, part-time faculty weren’t permitted to supervise an honours thesis. Negotiations made it possible, through a process of approval involving the department chair and dean.

Nikita Spencer is a second-year honouring in psychology. After taking a course she really enjoyed, Spencer approached the professor about a topic she was interested in for her honours thesis. She later discovered the professor was part-time and couldn’t advise her.

“It was super disappointing,” Spencer said.

“She would have been super supportive and would have helped me every step of the way. It made me question my decision to do an honours.”

She said there are only a few professors who are specialists in that specific area of psychology, so it limits her options.

Part-time professors who teach a heavy course load receive a permanent office space. Those with a smaller number share a part-time space with many other people.

Fleming shares an office on campus with two other part-time professors. He said meetings with students can be difficult and disruptive and there is no quiet space to do research.

“It feels like an equity issue,” he said.

“When I come in and I’m in this office and there’s three of us here, and I go to a full-time colleague’s office and it’s nicely decorated and there’s a comfortable arm chair, it’s kind of like, ‘Oh, that would be nice.’”

Fleming said the current situation limits what students can discuss with professors, especially when it comes to personal issues, which is difficult to begin with.

Spencer said the office hurdle has impacted her education.

“They’re not always there and once you’re [in the office] you kind of have to fight for privacy,” she said.

Teaching at two universities

In addition to the courses he teaches during the academic year, Fleming teaches four over the summer. A full-time professor typically teaches three in one semester and two in the next.

But STU will only allow part-time professors to take on a maximum of three courses, so Fleming and others to try to teach down the hill at the University of New Brunswick.

Last semester, he taught three courses back-to-back, the middle course at UNB, and the other two at St. Thomas, leaving him with 10 minutes in between to travel and get ready.

Fleming said it was challenging. Students couldn’t approach him after class and he had to abruptly change subjects.

Professors at STU are consulted about schedules, but nothing is guaranteed. Courses are based on department demands, which sometimes means losing out on UNB courses.

“It’s a real benefit to a lot of us that there’s a second university,” Fleming said.

“Because for those of us that have managed to build a relationship with both universities, there’s generally enough courses to make it work, but it comes at a pretty substantial cost.”

Though assembling schedules can be challenging, the union’s part-time collective agreement guarantees most regularly teaching professors like Fleming a set number of courses.

Despite this, Fleming still believes there’s uncertainty in being a part-time professor that prevents long-term career planning.

At any time, a part-timer can be told there are no courses available for them or their appointment has been cut back due to less operating funds, declined enrolment, curriculum changes, new full-time employees or changes in course offerings.

The university has no plans to reduce the number of regular appointments, according to Carleton.

‘Cycle’ of a career part-timer

Many professors don’t know from one year to the next what they’re going to be teaching. This makes it hard to say no to an opportunity, even if it’s a topic they aren’t interested in or one that might take a lot of preparation.

For part-time faculty, prep time is unpaid. Fleming said if he had a new course in January, a good portion of his Christmas break would be spent preparing for it. A full-time colleague, on the other hand, would be compensated.

Full-time professors typically don’t teach in the summer, allowing time for research and course development. But part-time instructors building a career need to teach during intersession and the summer to make a living.

“We all have research ideas that we’d like to pursue, but most of us simply don’t have the time to do so,” Fleming said.

He said the lack of research and published work by part-time professors is often used as justification for not getting hired for a full-time position.

“It creates this situation where you’re doing what you have to do to survive, but at the same time, you’re almost disadvantaging yourself from any prospect of a full-time job later on, because you’re not publishing, you’re not doing those things that are central to academic life,” Fleming said.

The 2016-19 collective agreement says full-time faculty can receive teaching reductions to focus on academic research, a request subject to approval from the department chair and respective dean.

But for a growing number of part-time professors, Fleming included, teaching whenever they can is their career.

“A lot of us get into this cycle of teaching part-time courses, where the more and more you teach, the less research you do, and in some cases the less connected you feel with the university because of it,” Fleming said.

Fleming could be doing his current job without a doctorate and has told students to think twice about pursuing a Ph.D.

“I think a lot of us, had we known this is how our careers would have ended up, we might not have chosen this path.”