Every Saturday morning, 12-year-old Marjorie Aitken visited the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts with her class. She loved art galleries and often went to see more with her parents.

The young Montreal girl had talent. She attended classes taught by Arthur Lismer and A.Y. Jackson, two members of the Group of Seven. She knew she was privileged to always be exposed to art – but it took her a long time to realize that she was an artist, too.

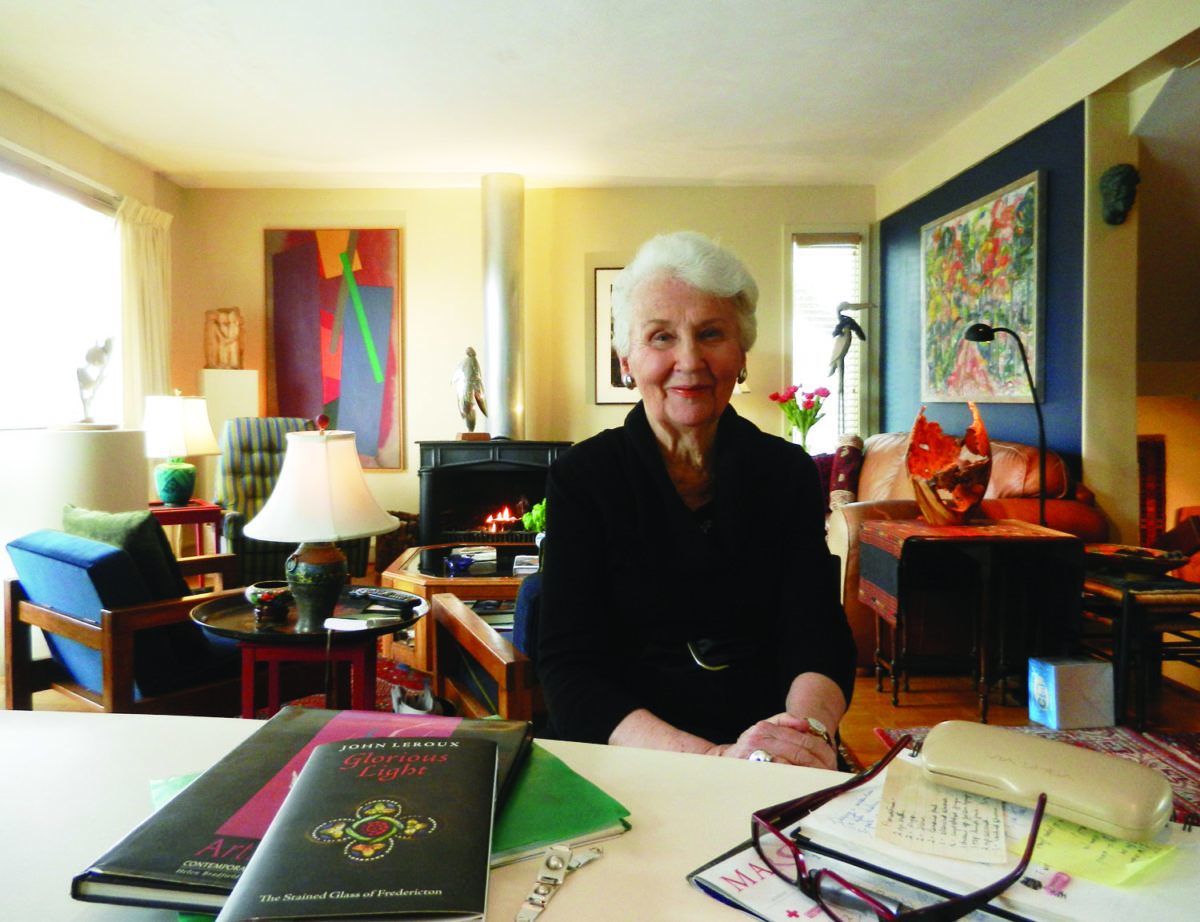

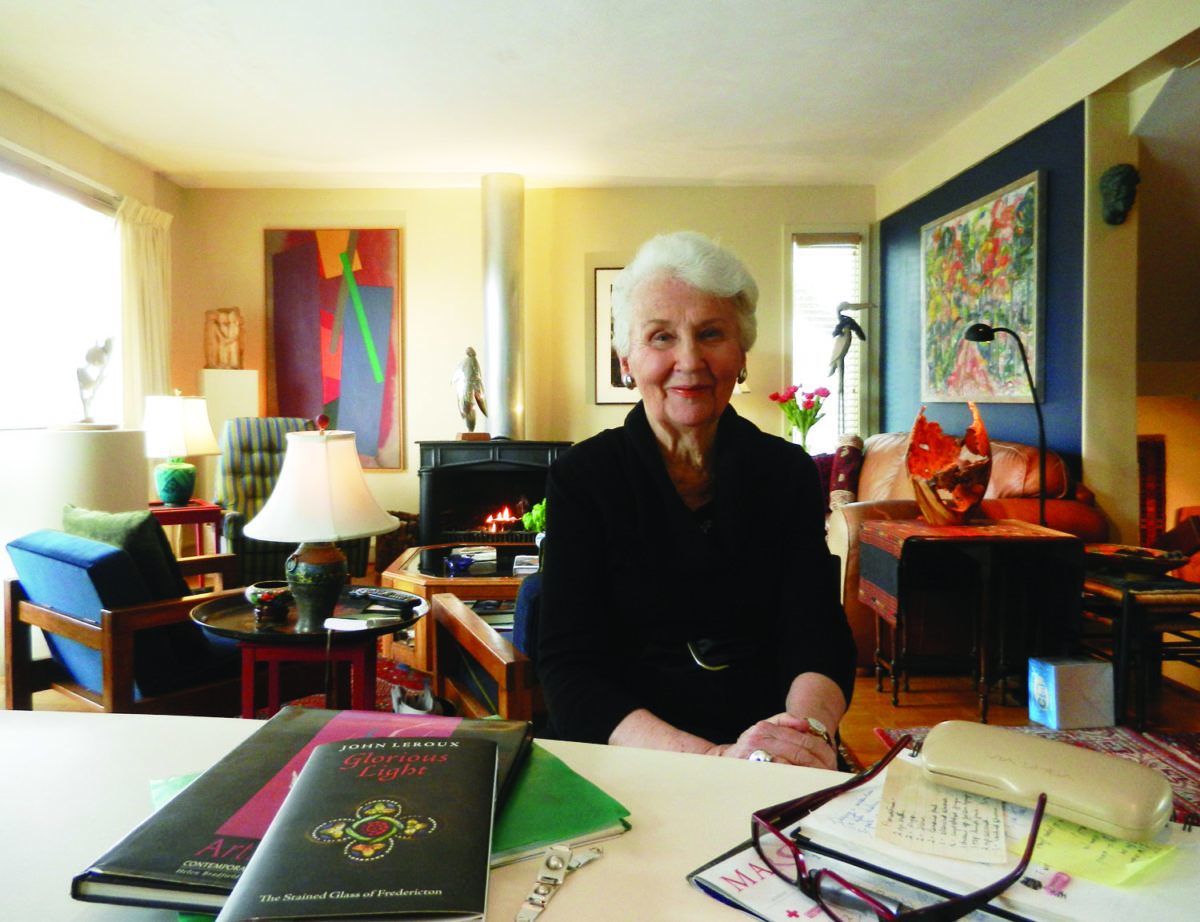

Today, the walls in Marjorie Aitken’s Fredericton home are covered with water-colours of flowers, French impressionist landscapes and chalk sketches. A fire crackles in an open fire place, classical piano music is playing from somewhere while she explains the meaning behind the stained glass window Virgin Mary in St. Thomas University’s chapel.

“The Mary of this window is a young pregnant woman, expectant, waiting, she holds the ball of the world in her hand, a world of red, brown, black, yellow and white races.”

A convert to Roman Catholicism, Aitken first started attending Mass at St. Thomas in the mid-1960s, because she preferred the cozy interaction after Mass compared to larger churches.

She noticed there wasn’t enough decorations or a Virgin Mary in the chapel. Before her design was made into a window in 1990, it was a felt banner she crafted.

“Mary is standing inside a room, which is by the edge of the sea, where life began and from which emerged Aphrodite, the ancient goddess of love and beauty.”

She started with a small sketch she enlarged and cut into felt pieces. The banner was almost done, but Aitken felt the picture was incomplete.

Then one day in church, it came to her and she told herself, “My glory, I didn’t bring her into the modern age!” So, she added a city to the image.

“The distant city can be interpreted as the Rome of ‘non nobis sed urbi et orbi,’ not for ourselves but for our city and the world a place [of] political and social action.”

Her banner of the Virgin Mary isn’t the only one Aitken made for the STU chapel. In the 1980s, she made felt banners and antependia (which hang over the altar) for weddings, as well as one that depicts the events of the liturgical year. She also made one for her daughter’s bookstore in British Columbia with a skyline of the Rockies and depictions of ice-skating and polar bears.

“In the playground of this world is a dual tree. It is the tree of knowledge around which twists the serpent tempter, and the serpent healer. It is also the tree of life whose fruit gives everlasting life and whose leaves are for the healing of the nations. On its branch sits a cockerel, a reminder of Peter’s and our denial.”

Baptized and married in an Anglican church, she became a Catholic in the mid-1950s. At that time, she had three small children to look after and went through a period of difficulties where she “needed extra fuel from somewhere.”

“In her humanity, Mary chose to listen to the word of God. As a child by the seashore, picks up a shell and listens to the sound, so the shell at her feet represents curiosity, inquiry and interior listening. A child’s pail and shovel play with the sands of time and our frail boats sail forth on a spiritual adventure.”

One day she visited the Catholic church near her home. The priest walked in and asked her with a Polish accent, “How can I help you, Mrs. Aitken?” His sleeves were rolled up, revealing numbers tattooed on his skin. She didn’t know he had been in a concentration camp.

They looked at the paintings on the wall. He asked her, “What type of pictures do you like?” She answered she liked French impressionists painters.

“Ah,” he said. “You’re a woman who likes the light.”

“Three circle, the circle of light, the circle of Mary’s motherhood and the circle intimated by the bird or the Holy Spirit are equal in size and distance to illustrate the Trinity of Father, Son and Holy spirit.”

He gave her books to read, but never tried to convert her.

Another day she was walking through the woods and he came towards her. He asked how she was doing.

“Whether I’m going to join your church or not, really doesn’t matter,” she told him. “Because I’m there already.”

“The swing is an image of where we are, or where we hope to be. Swinging in from a world outside the definition of this window, the swing is motionless until moved by the Spirit of the Child within, who will grasp and articulate a new vision.”

Putting away the art collection books, Marjorie Aitken says she spent two weeks straight painting last summer and already plans to repeat it this one.