Content warning: This story mentions murder.

A family from Red Pheasant Cree First Nation discusses how systemic racism and injustice allowed the man who killed one of their own to walk free in Cree filmmaker Tasha Hubbard’s nîpawistamâsowin: We Will Stand Up.

The film originally debuted at the Hot Docs Canadian International Documentary Festival in Toronto on April 25, 2019 and was shown to a Fredericton audience on Feb. 21 at the University of New Brunswick Faculty of Law.

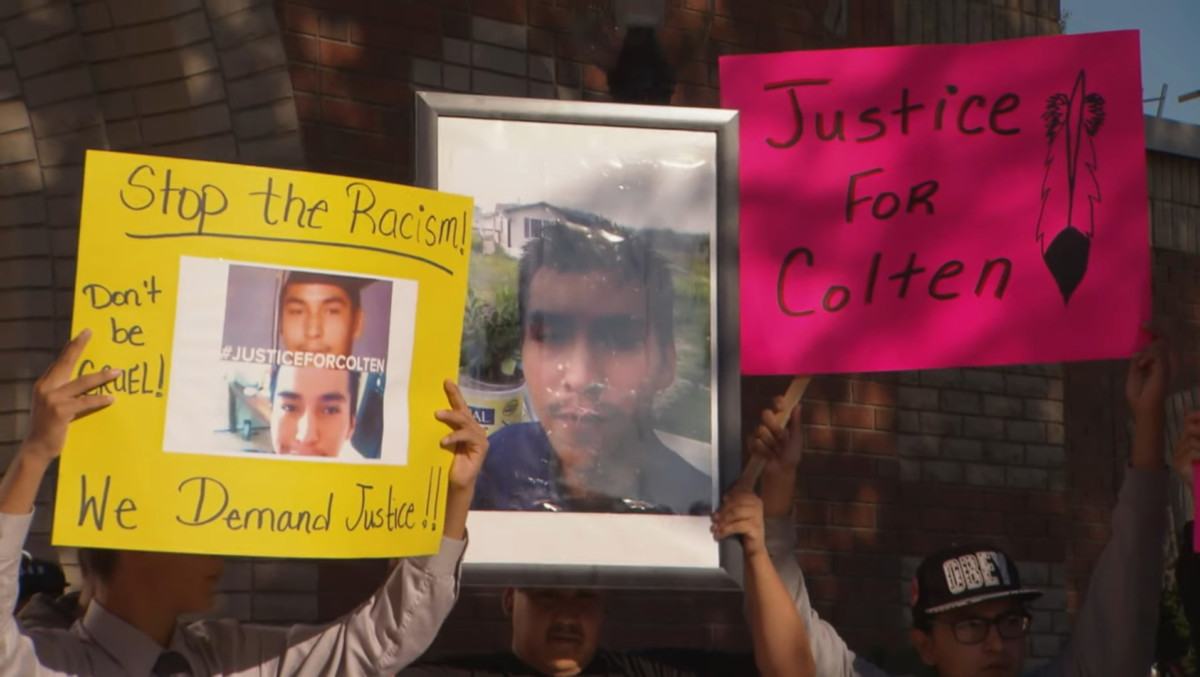

The film follows the true events of the death of Colten Boushie, a 22-year-old Cree man from Red Pheasant Cree Nation who was shot and killed by Gerald Stanley after Boushie’s friends drove onto Stanley’s farm in rural Saskatchewan.

According to a CBC article, Boushie was described by his community as a “cultural young man,” was an active participant in his church and had just finished a firefighting and life skills community program.

During the film, Boushie’s family wants justice and hopes Stanley will be charged with second-degree murder or manslaughter. But, the incident was mishandled: The RCMP left the evidence out overnight in the rain to wash away. To top it off, the legal system then secures an all-white jury and through racism of the courts, Stanley is acquitted.

According to Variety, an online entertainment magazine, Hubbard said the Boushie family agreed to participate in the creation of the film because they wanted to be proactive towards preventing further tragedies like theirs from happening in the community.

“They don’t want other families to go through something like this; they want our children to be free and safe.”

She added in an interview with the Inspirit Foundation, an Ontario-based public foundation, that the family’s determination to use their hardships to create change motivated her throughout the film during times when the production became tiring and overwhelming.

“I felt a lot of admiration for them,” said Hubbard.

“Life is hard as it is but to have to go through something like that and see the way Indigenous people are viewed within systems — it’s also really heartbreaking. I just decided to turn that feeling and that experience into the film to try and bring people to an understanding of what that was like.”

Nicole O’Byrne, an associate professor with the Faculty of Law at UNB, spoke at the screening and said the film is not an easy watch, but a necessary one.

“This is a tough documentary, okay? It’s tough for Indigenous people. It’s tough for non-Indigenous people because what you’re going to see here is a country that has not had the conversations that it needs to have with respect to race relations.”

André Loiselle, dean of humanities at St. Thomas University, gave a small lecture after the film screening to discuss how it would be approached from a film studies perspective.

“We have a sense of containment and separation that is presented to very constricted spaces like the courtroom when Stanley’s trial is held, as well as other spaces such as the RCMP Heritage Center,” said Loiselle talking about the documentary’s cinematography.

“That world is where they find themselves through half of the film. The other half is a sense of collective openness, versus a sense of intimate individualized containment.”

Hubbard focused on a small group of characters so the audience can follow along easier.

She also chose to include animated scenes in the film, brought to life by animator Justin Stephenson. At the very end, a full-body animated version of Boushie appears after the audience has only seen photos and short selfie-style videos of him up to that point.

“He stands there as a full person in a full environment,” Loiselle said.

“And [Stephenson] achieves that through animation.”

With the Indigenous rights issues occurring in Wet’suwet’en territory and Canadian-wide rallies, everybody needs to witness a story of injustice towards Indigenous Peoples.

If you have information about or want to report a missing or murdered Indigenous person in New Brunswick you can the helpline 1-833-MMI-FIND.

With files from Johnny James.