Warning: this story contains graphic content that may disturb some readers.

Marilyn Ingram of Elsipogtog First Nation said she carries guilt and trauma from her experience at Shubenacadie Indian Residential School.

“They would come and take you away in the night and I wanted to protect my younger sister. I’d take her and put her in the bed with me. I heard the other kids, boys and girls crying and screaming … I didn’t go help anybody because if I left the bed, they’d find my sister,” she said.

Ingram became afraid of heights after an experience she had with a priest when she was a child.

“We were scrubbing the stairs … this other little girl and I. The priest came up and he kicked the soap. He called us a bunch of names and then he picked me up and hung me over the railing. He proceeded to rape me. I was looking down the railing to the stairs and since then I’m terrified of heights.”

Ingram was one of three residential school survivors who shared their stories on Oct. 11 at the Honouring Our Survivors panel hosted by the University of New Brunswick Student Union and the Mi’kmaq-Wolastoqey Centre.

The Shubenacadie Indian Residential School was sanctioned and paid for by the federal government to promote a solution to what it deemed the “Indian problem.” Staffed by church clergy, the residential system was mandatory for all children born with status under the Indian Act.

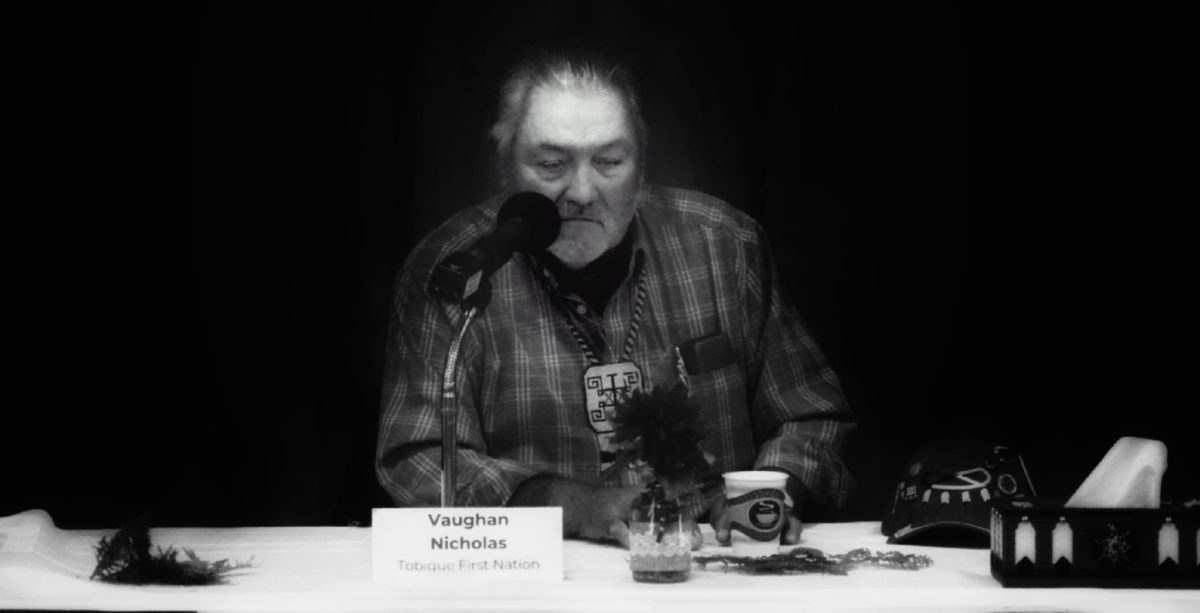

Vaughan Nicholas of Tobique First Nation, another panelist and survivor, said he doesn’t blame the general public for the residential schools.

“Some people don’t even know residential schools ever existed and some still believe that it was for our good. [They thought] that we were being educated, being taken care of and that the nuns and priests were supposed to be loving and caring. They were hired to do a job and it was to try and assimilate us,” he said.

Vaughan Nicholas and his sister survived Shubenacadie. He said it was like a prison.

“We were incarcerated and it was regimental living where if anything was out of place … nun’s liked their straps. They had this string around their robe where they had their straps or a [stick] ready to use and mostly on the young ones. These were the enforcers … they heard anyone speaking their language and bang, you got it.”

“One time a boy messed his pants because he had this virus. A nun beat him for doing so, so I came to his defence trying to tell the nun ‘esoposu,’ that he was sick, and she hit me because the word for diarrhea wasn’t in my vocabulary,” he said.

Iris Nicholas of Tobique First Nation discussed intergenerational trauma and the impact of abuse.

“They were trying to take the Indian out of us. They used their God a lot and made us fearful,” she said.

“We were trained from the time we woke up to the time we went to bed.”

“They were training us and controlled us to live as they did. The first day I was scared to death and I never knew I was traumatized until a few years ago.”

The staff would beat and starve students over alleged sins. Children were tied to beds and forced to commit humiliating acts.

Ingram also explained how elected ministers responded to the sexual assaults, and claims of abuse.

The Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement acknowledges the damages inflicted by residential schools and established a multi-billion dollar fund to help survivors recover.

“They said that they asked for it, they said that they lied, that we wouldn’t know how to handle [financial compensation],” she said.

Ingram said the abuse continues today — from attacks on culture to violent abuse.

“It’s not just us — look at the orphanages, look at the correctional services, look all around us. The worst thing you can do is to look back complacently and think that this is not going to happen to your children. Because for all you know, it already is.”

Vaughan Nicholas cried while talking about how he lost a son and a nephew to suicide. He wants to continue educating people and working toward reconciliation. But he’s not sure he’ll see that in his lifetime.

“I think Canada should be held responsible for what they did spending millions trying to take our language away and now there’s no money to try and bring it back for our kids. I know that for people to coexist we need to respect each other,” he said.

Iris Nicholas also wants to educate people on what happened to herself and other survivors.

“Physically it didn’t bother me much, but mentally and emotionally I’ll never get those memories out of my mind … I want to educate people.”

After Iris Nicholas was free from the school, she became dependent on alcohol.

“I hated being an alcoholic. Now I carry the guilt of not being a parent to my children. I fed them and clothed them, but I did not know how to talk to them. My kids had to go through that and I loved them. I did not know how to deal with them,” she said.

“Now I think of the children and women … it’s a traumatic way for a child to grow up without a mother or father. I felt unwanted and abandoned and that stuck with me. When I talk about this, I can’t hold it back I’m there again, and I’m a child again.”