With an unprecedented number of heat waves hitting Fredericton this past summer and a Halloween night that broke heat records in the city, that were held since 1901, climate change is a topic that has been on the public’s mind.

Some researchers are pushing nuclear energy as the solution, but not everyone is convinced.

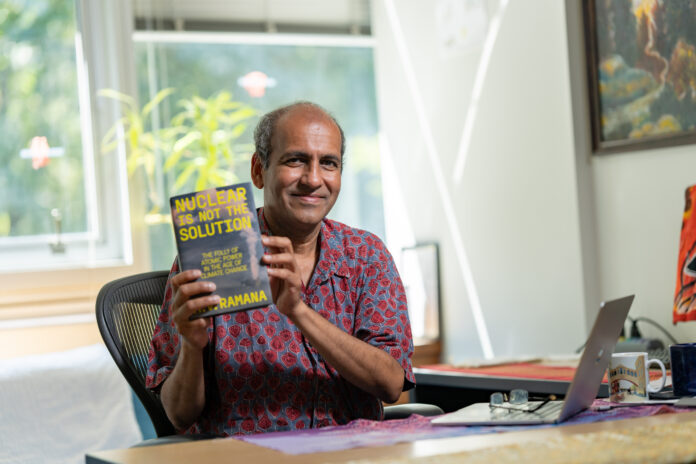

In July, M. V. Ramana published Nuclear is not the Solution, a book that destroys the illusion that nuclear energy is beneficial to fighting climate change.

Alongside Ramana, three St. Thomas University students – Emma Fackenthall, Erin Hurley and Kate Haché – worked on the project as research assistants and hosted a webinar on Oct. 10 on nuclear energy.

As a professor and Simons Foundation chair in disarmament, global and human security at the school of public policy and global affairs at the University of British Columbia, Ramana has worked on various topics related to nuclear energy throughout his career.

“This topic became important for me to address, partly because I had already assumed that it would be quite obvious that nuclear energy is a very problematic source of power,” he said. “It is capable of severe accidents like what happened at Chernobyl and Fukushima and nobody in their right mind would be considering building more nuclear power plants.”

He said it is relevant to draw attention to this topic because people have begun positioning nuclear power as the solution to climate change without looking at the history and technical aspects that make it unsuitable, such as the costs and potential risks.

While there may not be a clear solution to climate change, Ramana said that “because the problem is global and caused by multiple factors, we need a very broad democratic consensus on how to deal with it and we don’t have that yet.”

Ramana described it as a “wicked problem” since it involves a broad set of aspects that make it challenging to agree on solutions benefiting everyone.

Fackenthall, a fourth-year student double majoring in English and environment and society, has a passion for the environment. Aside from working on Ramana’s book, she also works for CEDAR — a five-year project studying energy transitions in Canada with a focus on New Brunswick, which Ramana is also collaborating on.

Like Ramana, Fackenthall has similar qualms with nuclear energy.

“Nuclear waste tends to create a lot of environmental racism, especially for Indigenous communities in Canada,” said Fackenthall. “A lot of energy projects tend to disproportionately impact their communities and pollute their lands.”

She said that the collaboration with the other assistants, Haché and Hurley was rewarding because everyone had “different perspectives to bring to the table,” which “highlights just how interdisciplinary the environmental topics are.”

Haché, a third-year student double majoring in economics and international relations, focused on the financial aspects of nuclear power and reactors, while Hurley, a fourth-year student honouring in environment and society and majoring in journalism, looked at the media coverage of energy transitions in newspapers like the CBC and The Telegraph.

Hurley shared her growing enthusiasm to advocate for renewable sources of energy rather than nuclear.

“I’ve been doing some research on this for a couple years and I still feel like there’s so much to learn about it,” said Hurley. “I definitely would like to continue this research.”