St. Thomas University’s Indigenous Student Reconciliation Committee hosted the final part of their Indigenous Education and Awareness series last Thursday, where they talked about Missing and Murdered Indigenous women, girls and two-spirit people.

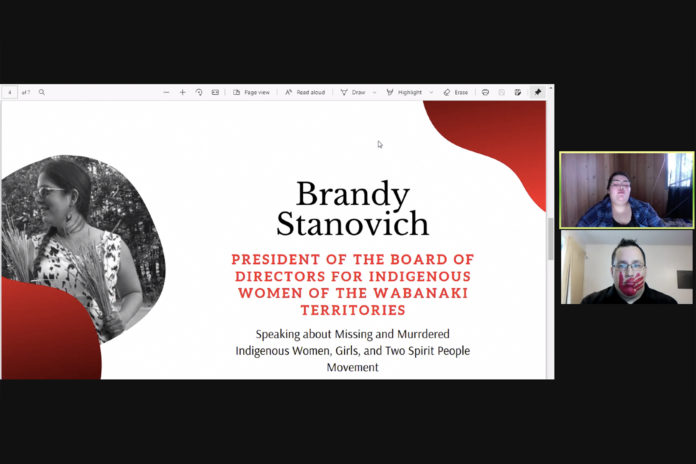

Brandy Stanovich, the president of the board of directors for the Indigenous Women of the Wabanaki Territory, was the guest speaker. She focused her discussion on the movement, statistics and the realities Indigenous women face in Canada.

“Our women are being murdered and taken at a rate 10 times higher than any other ethnic group in the world,” said Stanovich.

One of the hosts, Jonah Simon, wore red face paint over his mouth as a symbol of solidarity with MMIWG2S.

The Indigenous Women of the Wabanaki Territory is a non-profit organization located in Fredericton formed to represent Indigenous women in New Brunswick.

“Our mission is to provide healing and capacity building to Indigenous women in order to promote and recognize their traditional leadership role,” she said. “We strive to improve the quality of life for all Indigenous women within our territories.”

Stanovich outlined the history of the MMIWG2S movement and shared various methods used to bring awareness, including community tribal, domestic-violence training vigils and monuments.

She focused on Sisters in Spirit – a reoccurring movement led by the Native Women’s Association of Canada since 2005. This event is held across the country to honour missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls and their families.

“The initiative has worked to identify root causes, trends and circumstances of violence that have led to the disappearances and deaths of Aboriginal women and girls,” said Stanovich.

She discussed the Faceless Doll Project, which commemorates the lives of the more than 600 missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in Canada through a collection of felt dolls.

Stanovich said this was a way to recognize their loved ones, but now, with a change.

“That’s the new movement for NWAC: putting a face on justice because we don’t want the women to remain faceless anymore.”

The NWAC’s key messages are reducing violence, economic security, access to justice and reducing the impact on children in care.

Stanovich said, in 2007, the United Nations Declaration on the rights of the Indigenous community was formed.

She said the UNDRIP is the most cited international framework used to address systemic discrimination and violence facing the Indigenous community. She outlined the timeline of different documents and frameworks, such as the International Framework ensuring Indigenous rights are respected and upheld across Canada.

“Today, we’re still fighting for a voice to be at the level of government that we need to talk to – to make a difference,” said Stanovich.

In January, she said, the NWAC – herself included – met at a national round table to respond to the calls of justice. She outlined significant findings and said a vital component of addressing this issue involves creating political, social and cultural changes that would enable women to reoccupy the value roles they had in their communities before colonization.

Stanovich said this includes an action plan in place for both short and long-term issues.

“That’s where I see the education system could have a play.”

She said, as Wolastoqey and Mi’kmaq people, they were a matriarchal society, and the settlers came, colonized them and took away the importance of women 500 years ago through their attacks.

“We have to decolonize. We have to change that way of thinking,” said Stanovich. “Our women aren’t being held in the high respect that they used to be and that hurts us today.”

She expressed the value of seeing Indigenous children having access to their language in schools and their communities, as she missed out on that experience growing up.

“That’s something that’s really close to my heart because, without your language, there’s no culture.”

Stanovich said she’s shocked by how many people are unaware about the missing and murdered women statistics and said the respect Indigenous women once received needs to be retaught to society – starting with the education system.

Indigenous women make up only four per cent of our female population, Stanovich said, but 16 per cent of all women murdered in Canada between 1980 and 2012 were Indigenous.

“There’s a lot of voices left unheard, there’s still women missing.”