Nestled near Otnabog Lake, between Saint John and Fredericton, lies the historic community of Elm Hill, one of Canada’s first Black settlements.

Previously known as Otnabog, Upper Otnabog and Pleasant Villa, Elm Hill was established by Black loyalists in the early 1800s, with immigrant settlers coming from the United States, mainly from Virginia.

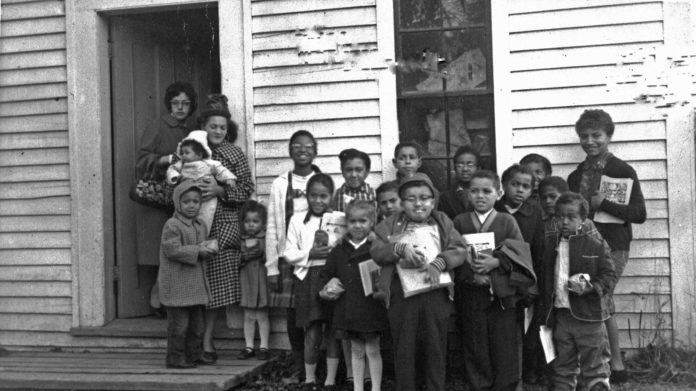

One of the plaques in the community depicts its churches as a tight-knit community. Church was an “all-day event,” including fancy dress and the sound of hymns soaring over the Otnabog Lake.

Though it’s a small settlement, Elm Hill was a prosperous farming town and developed its economy, thanks to the steamboats that travelled on the river to transport people and products.

Once home to two churches, a school and a post office, Elm Hill has been on a slow decline since the 1960s. Many farmers moved from the remote community to urban areas when the railroad replaced the river traffic. The settlement slowly crumbled.

Now, the town is home to only about 50 people, though historians and archivists recognize its importance to the Black community in Fredericton.

Meredith Blatt, an archivist in the private sector records with the Provincial Archives of New Brunswick (PANB), said many well-known Black New Brunswickers can trace their roots back to Elm Hill.

“It was one of the early communities,” said Blatt.

Blatt said PANB strives to work closely with New Brunswick’s Black community in order to preserve its history. However, much of Black history in New Brunswick remains untold.

Names like James “Skip” Arthur Talbot are an integral part of Black history in New Brunswick. Born in Truro, N.S., he spent a lot of his career in Moncton, and Blatt described his service to multiculturalism as “impressive.”

“He was one of Canada’s first Black radio operators with Transport Canada,” said Blatt.

One of Talbot’s endeavours was to help the Black community of New Brunswick share their stories. He helped organize a reunion to Elm Hill each year, where those who had family ties to the land — and those who did not — would come together to share stories.

In 2019, Talbot hosted around 50 people on his grandmother’s land.

Other notable citizens of New Brunswick include Edward Mitchell Bannister, an artist from St. Andrews, who spent much of his career painting in the United States. Arthur St. George Richardson was the first Black man to graduate from the University of New Brunswick.

Blatt said it’s important for people to go looking for the history.

“Even just finding out places around Fredericton where Black communities lived and thrived,” said Blatt.

“We’re really lucky we have quite a series of oral histories, recordings that were done in the ’90s of residents who could trace their roots back to [Elm Hill],” said Blatt.

In more recent years, the likes of Mary Louise McCarthy-Brandt and Roger Nason are continuing their work to uncover the New Brunswick Black community’s history in full.

McCarthy-Brandt has spearheaded a project called Remembering Each African Cemetery’s History (REACH), which aims to locate and record gravesites of Black people in the province. Nason continues research on the province’s history, including on loyalist settlements similar to Elm Hill, like Loch Lomond.

In his “Economic Exploitation of the Black Refugee Settlement at Loch Lomond, New Brunswick, 1836-1839,” Nason notes that while loyalists were issued “licenses of occupation” for land, many were not converted to land grants for over 20 years.

Colonial authorities often forced responsibility for all survey costs onto Black settlers. According to Nason, this made it “practically insurmountable” for Black settlers to meet the requirements of the license of occupation.

Many Black settlers were driven to find other options to live in Saint John or sell their land to white settlers and businessmen.

It’s for this reason that Blatt emphasizes the importance of storytelling.

“We need to keep telling these stories, keep finding out more information about them,” said Blatt.