“We can’t have beans for Christmas dinner,” my mother pleaded.

You could see the wheels in her head turn.

“We should all go out for supper…I should call for reservations,” she said before jumping towards the phone.

“You don’t have to do that,” snapped my dad, his mind racing my mothers now.

“We have plenty of good food going to waste freezing outside our door,” he continued, calming his voice.

“Bean’s will be fine, we don’t need a mess when it’s hard enough to do normal load of dishes.”

Only days before Christmas, the storm caught our small town of Quispamsis, along with the rest of New Brunswick, completely off-guard, leaving more than 50,000 homes without power. Gas generators disappeared from stores within the first night. Those houses lucky enough to own one were targeted with dirty looks by every passing car who spotting any sign of light in a far-off window. If they wasted their precious power on Christmas lights, there would be no forgiveness.

Heat, water and plumbing cut out our electronics, our Internet; every single distraction, escape and buffer at our disposal disappeared along with our sparkling Christmas tree. It’d be four days before we saw our streetlights glow again and Christmas would pass without power.

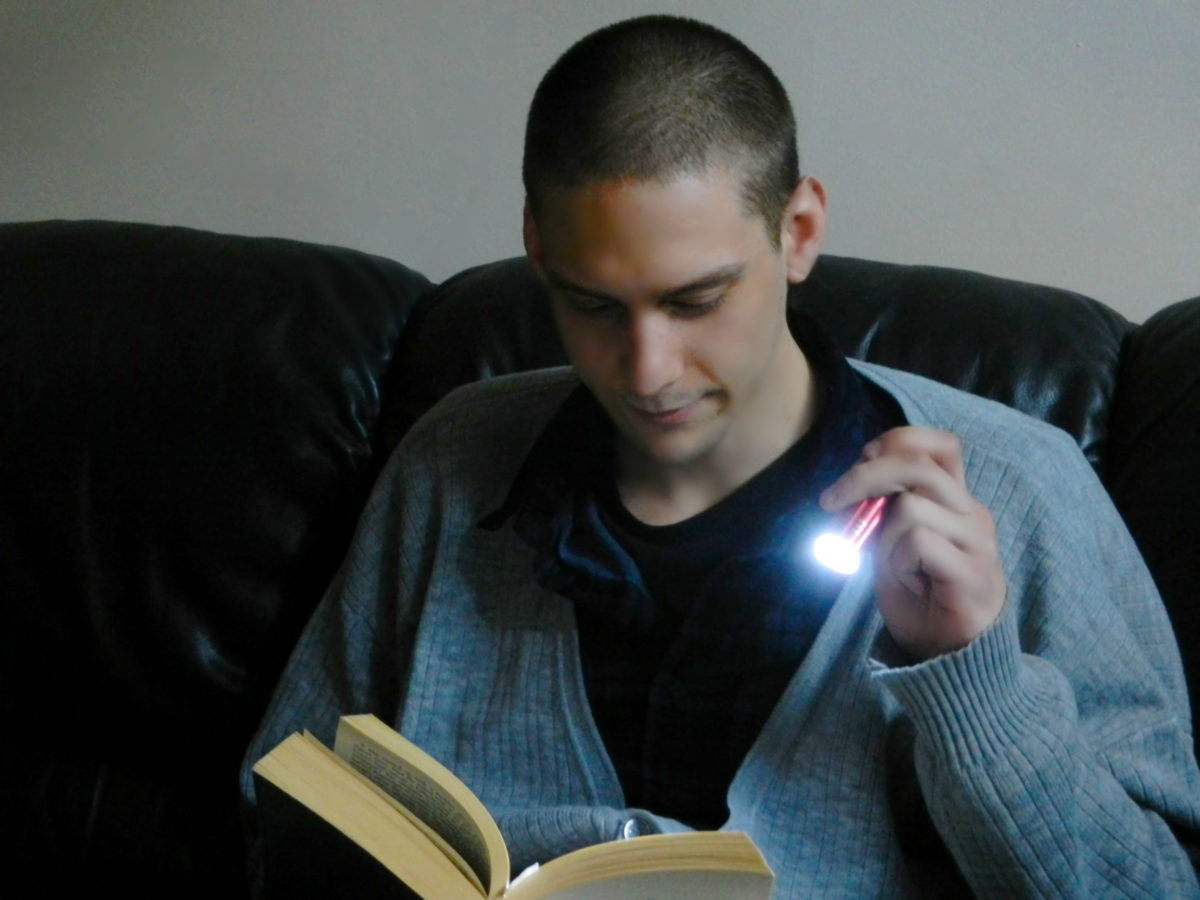

We were left with what little food didn’t freeze outside our door, a half-dozen scented candles never meant for lighting, and an assortment of flashlights we’d continuously forget when moving from room to room. We’d have to double back in the dark if we braved any part of our house but the basement, which had been built around an iron wood-stove, now single-handily heating our entire house.

As days passed without the return of power, my mother grew distraught. She’d planned a tasty seafood chowder for Christmas Eve and a turkey for Christmas Day. We’d long since learned to cook simple meals on the stove — mostly limited to canned beans, fried eggs and toast – which would be fine, if it wasn’t Christmas.

•••

Christmas at the Robichaud residence was never simple and had only grown more complicated over the years. Santa Claus has long been buried and with his death came the realization that the magic of Christmas came with a price tag. My father’s callous hands and lined face, pinned in place by a scruffy grey and white mustache, represented the truth behind the season better than any decoration could hide.

My mother, on the other hand, loved Christmas. She’d spend the entire year, every year, picking out gifts for the rest of us while we would wait until the last minute and end up picking out her gift in a state of panic. She bought all our decorations, often decorated the house herself, planned and cooked Christmas dinner.

This year, I wanted to do more for my mother. With my one-time-a-year special supper on the line, I knew just what I would do.

“I don’t see any reason we can’t cook the seafood chowder on the stove like we’ve been doing all along,” I said to my dad that morning.

“I’ll cook it.”

His scruffy brows rose in surprise. The Lion had set his sights on me. His mouth settled into a straight line, pulling his bristled mustache with it, before letting out a deep sigh only a man with infinite patience can make.

“You’ll never get the potatoes to boil,” he said finally.

“I’ll cut them into small chunks. I’ll look after it. I’ll make it work and take responsibility for it.”

“You’ll be stuck in the basement looking after it all day if you do that,” he said in his final attempt to dissuade me and he was right.

I stood firm. I didn’t mind. I was already happy caring for the fire, replenishing the water – why not cook Christmas supper while I’m at it?

•••

So, I called my mother for the recipe, took the largest pot in the house, filled it with what little drinking water we had, chopped the potatoes into awkwardly shaped chunks and began the long fight for the flavour I had been dreaming of since I last left home cooking.

The endeavour took most of the day even with the help of my father and my brother’s suggestion of feeding the remains of the apple tree our father had chopped to the fire. Who’d have thought it would burn so much hotter than spruce or birch?

In minutes, the slow bubble I’d nursed for hours exploded into a boiling maelstrom. Fresh bacon and mixed fish sizzled beside the large pot, filling the basement with the aroma I so longed for. With it came my father and my brother, and together we nursed the chowder to life.

That night by candlelight, jokes and compliments were shared, stories told; my brother and I sang songs to the sounds of my brother’s acoustic guitar, read from Doyle and Hemingway for our parents to enjoy. And not once did I miss my Christmas lights.