The province is in a stand-off. Environmental activists are asking for the protection of the province, while people who approve shale-gas exploration are saying that the risk is worth it. Which side is right?

The Aquinian sat down with Adrian Park, a member of the science committee at the New Brunswick Energy Insitiute and earth sciences instructor at UNB, and Janice Harvey, a environmental science professor at St. Thomas and former president of the New Brunswick Green Party, to find out their answers to these difficult questions.

Is hydrofracking a danger to the water supply in New Brunswick?

Adrian Park: If the process is carried out properly, the risk to groundwater and surface water supplies is minimal. Direct leakage of slick water (the water-sand-chemical cocktail used in the hydrofracturing processes) from a fractured shale layer is not the largest risk, and the deeper the process is carried out the less chance this has of happening.

The largest risk of leakage into groundwater of slick water comes from poorly constructed wells, a problem to be addressed for all oil and gas wells whether fracked or not. “Industry best practice” regulation and enforcement minimize this risk, and there is active research into improving existing well integrity.

Surface spillage of stored slick water can be an issue, but quantities used can be reduced by recycling recovered slick water. Waste water is currently transported to a licensed treatment plant in Quebec. Should the industry expand, then a provincial treatment facility would be necessary.

Janice Harvey: It is a danger to water supplies wherever fracking is done. Underground water supplies and wells are contaminated in various ways through the fracking process. This includes from the storage and disposal of the contaminated water that returns to the surface after the fracking is done. A percentage of fracking wells do fail. For example, the well casings crack allowing methane to escape into the water table and from there into surface waters or wells. It’s important to remember the fracking process itself requires a vast amount of fresh water, which toxic chemicals are then added, and so existing fresh water supplies are diverted for this industrial use.

Typically with environmental hazards such as this, those who benefit the most financially actually bear the least risk when (not if) something goes wrong. Even the fracking companies admit that their industry is not risk-free. Thus, there is a need for constant protests and demonstrations to make their voice heard.

What impact would shale gas have on global warming?

Adrian Park: This would depend on how the gas was used. Methane has the lowest CO2 emission per energy unit of the hydrocarbon fuels. Used for electricity generation, CO2 emissions from natural gas burning can be as low as 40 per cent released from coal burning and around 60 per cent from oil. If natural gas is used as part of a combined heat and power operation, the savings can be higher still. If we used shale-gas to phase out the two oil-burning generating plants, it would have a significant impact on the provincial carbon footprint. If the gas were used by domestic and industrial consumers in the province and replaced oil use, a reduced carbon footprint would also be the result.

Janice Harvey: The only way shale gas development in New Brunswick would not contribute to the problem of global warming is if greenhouse gas emissions from other sectors were reduced in the same proportion. Further, scientists tell us that we have to reduce our GHG emissions globally by 80 per cent over the next few decades if we are going to avert “dangerous climate change.”

The International Energy Agency has said if we are to avoid dangerous climate change globally, no new fossil fuel infrastructure should be built. Shale gas wells and pipelines are new fossil fuel infrastructure. Once built, they lock in an economy to their use – with all the environmental and social implications attached to that use – for several decades. Politicians who ignore these warnings are either in deep denial, or they are being willfully reckless and acting unethically.

How much land in New Brunswick could end up being drilled? What’s the potential environmental impact on the surface?

Adrian Park: There are two areas in that would be impacted. The Sussex-Moncton-Hillsborough-Dover area contains potential gas-bearing shale at depth and already contains the Stoney Creek oil and gas field and the McCully gas field near Penobsquis. The second area runs from the north shore between roughly Cap Pelee and Miramichi and inland to the west (the area licensed for exploration to SWN).

Individual gas drilling and hydrofracturing operations require a site of three to five hectares to encompass drilling equipment and storage for process and slick water, but once a site is producing this area is considerably reduced, perhaps one to two hectares. Provided sites have been constructed and operated properly there is no reason they cannot be returned to original use when the gas extraction is finished.

Janice Harvey: This would depend on the extent of the shale deposits and their commercial viability. The experience in the U.S. shale plays is that wells have the highest production in the first year or two and after decline dramatically. In order to stay profitable, companies have to keep expanding their footprint through multiple wells on a pad, and then through constantly building new pads. If you search the internet for aerial or satellite photos of fracking zones, you will find the most disturbing images of entire counties peppered with well pads. The economic incentive for a company to keep expanding depends on how quickly the production at a particular well pad drops below what their profit expectations.

What are the dangers of using seismic testing to discover what’s underground?

Adrian Park: Seismic exploration techniques either use explosives or “thumpers” (hydraulic rams that “thump” the ground) to generate acoustic signals through bedrock. Other than the danger involved in operating large vehicles, there are no known hazards associated with this activity. Seismic exploration only images the bedrock, revealing layers and structures below ground that may contain gas-bearing shale – it cannot identify shale gas deposits.

Licenses in New Brunswick are staged. A company wishing to carry out seismic exploration must apply for a license. If the process moves on to exploratory drilling, a new license is required. Production involves yet another stage of licensing. Each stage involves Environment Impact Assessment and public hearings can occur in response to each application. The idea that once these companies are in the province development is inevitable and we’ll never get them out is a myth.

Janice Harvey: Seismic testing itself can damage wells, foundations and other rigid structures. But the bigger issue for people is that the way the licence process is set up in New Brunswick. If a company finds commercial deposits of shale gas during the exploration phase, the government is obliged to then issue them a licence to develop it. Of course, the government will say that before this happens, an Environmental Impact Assessment would be done on the proposed development. But this is just a formality. The EIA process in New Brunswick is little more than a rubber stamp. The best it could do is to place certain conditions on the project that would attempt to reduce its impact. Further, New Brunswick has a terrible record for enforcing environmental rules. And in any case, no conditions would eliminate the multiple environmental risks associated with the industry. This industry can never be made ‘safe’ and anyone who tells you it can is either lying or deluded. The effort can only be to minimize risk.

What is the economic potential of shale gas in New Brunswick? Is it worth the risk?

Adrian Park: Current estimates of the amount of shale-gas in place in New Brunswick are around two to three trillion cubic metres. These are significant and potentially valuable deposits of natural gas, and much of the pipeline infrastructure is already in place. Against this stands the fact the price of natural gas in North America is at a 30-year low. In the end, economics will decide the issue.

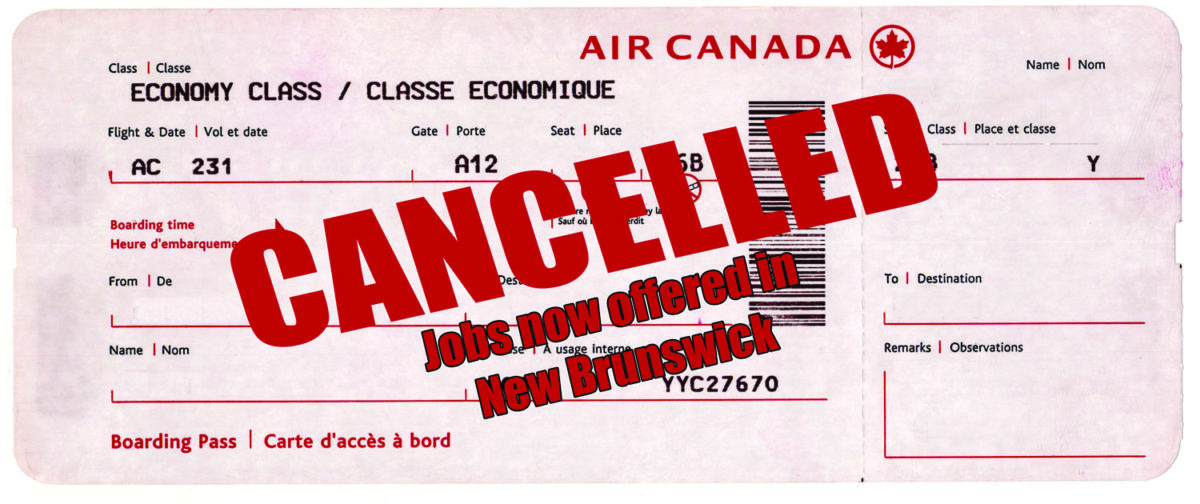

There is risk involved in every industrial enterprise and energy projects can have large impacts on land use. My own belief is this is where shale-gas could have the biggest impact on the provincial carbon footprint, and in generating employment and revenue. Given the current transfer payments on which the province relies for around 40 per cent of its revenue, any indigenous source of revenue should be welcomed. Our second largest export as a province is our young people. An industry that would keep these skilled young people here – earning good wages and paying taxes here – should be examined carefully.

Janice Harvey: My comments already address this.