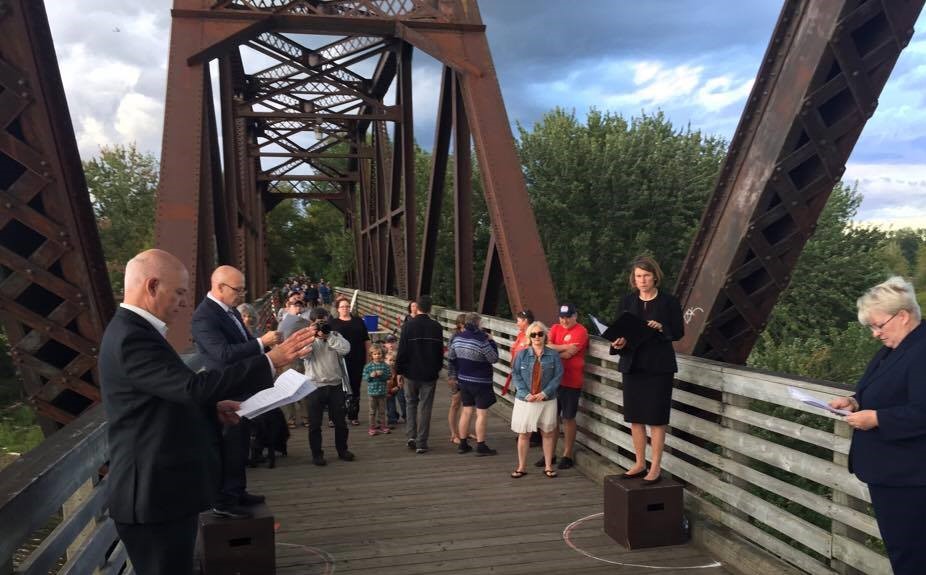

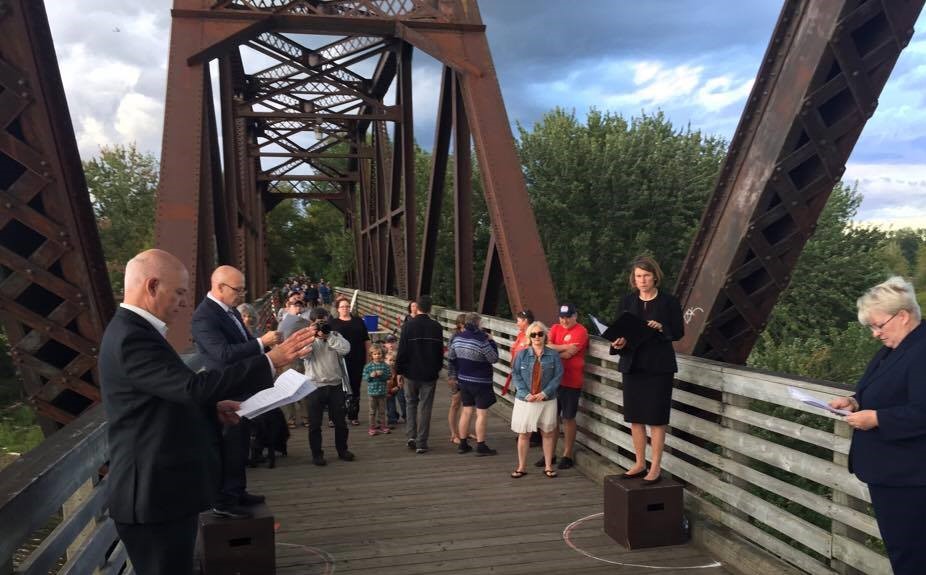

Solo Chicken Production’s The Bridge Project gave Frederictonians an eye-opening look at Canadian identity on Fredericton’s Bill Thorpe Walking Bridge Friday evening, despite rain forcing it to end it an hour early.

The project involved 54 artistic displays stretched along the walking bridge, each representing a certain piece of Canadian culture and history and arranged in random order. Viewers walked through the bridge in what some described as “a living time-tunnel” of works that included songs, skits, artwork, dances and literature readings.

The Bridge Project was the company’s answer to a Canada 150 celebration after the company’s director Lisa Anne Ross was faced with the moral dilemma of the anniversary.

“She knew there was a lot of controversy surrounding the 150, and she knew the 150 was problematic for those very colonialist undertones,” said Solo Chicken’s media coordinator Alex Rioux.

“To her it was like, ‘Well, I have a voice and I have this platform, and I might as well use it to start a discussion,’ because if you’re not saying anything about it then you’re also not challenging it, so she wanted to do something that would challenge the 150.”

Using photos from the New Brunswick Provincial Archives, the company reached out to local groups and artists to create pieces based on these snapshots. Displays like “What Is Drag?” and “Len and Cub” explored the LGBTQ roots in Canadian history, while “Stories of our Culture,” facilitated by Kelly Baker, painted a diverse picture of what being Canadian means to many young newcomers.

Pieces were also donated by members of the community to add personal perspectives on what it means to be Canadian. No One Is Illegal – Fredericton, a migrant justice group, displayed hand-written welcome letters from local families to Syrian refugees in the piece “Welcoming Words,” while local artist Penelope Stevens created a childlike reimagining of a paper mill to reflected her own experience as a mill-town child in “Stinky Mill Making Stuff.”

Artists paid respect to Wolastoqiyik territory by dressing in full regalia, tying sacred strips of red cloth along the bridge as a reminder that Fredericton was built on their land. Other demonstrations, like the dance-prayer, established the sacredness of water in Indigenous cultures, and was performed in a traditional Wolastoqiyik jingle dress.

According to Rioux, the significance of the project was summed up by the bridge: to reflect the coming together of times and cultures while remembering the industrialism and colonialism that helped put it together.

“This isn’t just a celebration, this is an interrogation. It’s the side of history that you don’t get to see enough of or that was intentionally erased,” he said.

The Bridge Project had many of the hundreds of attendees praising its relevance and detailed scope.

“It had me feeling all kinds of emotional,” said Emma McCorkell, a St. Thomas University student who heard about it on social media.

“It’s proof that a collaborative effort can become something so beautiful.”