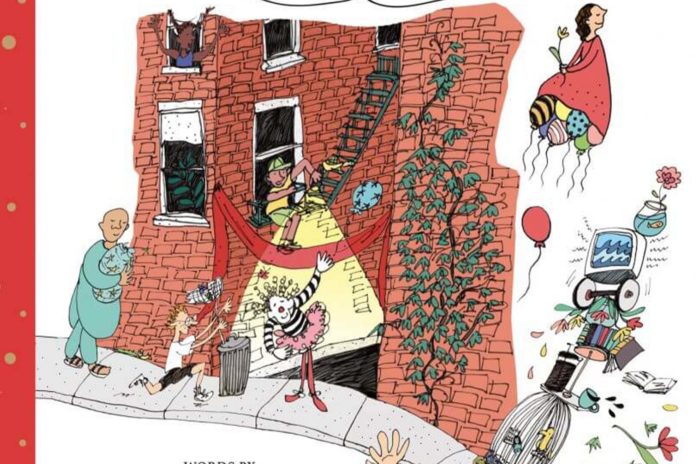

EveryBody’s Different on EveryBody Street is a children’s book by Canadian writer Sheree Fitch. Fitch uses eccentric illustrations and rhythmic poetry to address human diversity and suffering.

The project was originally released in 2001 as a mental health pamphlet, serving as a classroom tool for teachers and children and a fundraiser for the Mental Health Foundation of Nova Scotia.

The work was initially burdensome for Fitch, due to her personal experiences with her son who lived with mental health conditions and minimal resources to cope.

In 2018, it was developed into a children’s book by Nimbus Publishing. The French translation was published by Boutons d’Or Acadie publishing, including a new afterword that recontextualizes the work in the wake of losing her son.

“I shed tears over that book because I believed every word I said,” said Fitch.

The book has capitalized “B” and “O” in the words “EveryBody” and “EveryOne.’ According to Fitch, the capitalization of letters in certain words are to give them second meanings.

“If we look at ‘healthy,’ most people don’t see ‘heal,’ but I do see that. I wanted [readers] to see the ‘many’ and the ‘one,’” she said.

Fitch is wary of writing children’s books with explicit messages in them and prefers to leave the content slightly vague.

“I think a good children’s book should be a book with a story first that captivates you … and if it’s a good children’s book, it should be as good for adults as it is for children,” said Fitch. “If you dumb it down [for children], you’re patronizing.”

She believes the conversation around mental health has changed since the book’s first publication in 2001, but that true progress around mental health is measured by access to resources.

“I’m glad a book can spark discussion but it has to be fixed with resources and action,” she said. “At the end of the day, we [must] save lives and heal those broken souls and get them the resources they need, when they need them, before it’s too late.”

Marie Cadieux, literary and general director at Bouton d’or Acadie and translator of the book, originally approached Fitch about the translation.

Cadieux said the translation of the work into French allowed for a deeper exploration of some of the book’s ideas through rhythm-based changes.

“I tried to work with rhymes … in French to deliver that singsong voice that is such a special trait of Sheree’s English writing,” she said.

Cadieux also brought the book’s emphasis on inclusion and acceptance to a new level through the French grammar. She used an equal balance of masculine and feminine words — a grammatical device that doesn’t exist in English.

Cadieux said translating is an art form and compared it to the way that musicians play classical works written by others.

“There’s a satisfaction in the reading that should bring the balance between having really followed and been loyal to the spirit of the book and original writer and at the same time, giving a voice and a full existence to the text in French,” said Cadieux, translated from French.