Dunkirk is France’s northernmost port on the English Channel, just below the Belgian border. A small industrial city with a winding harbour and strange Flemish street names, the world knows it as the evacuation point for Allied troops fleeing the Nazi armies in 1940. Today, Dunkirk raises new images of huddled masses desperate to reach England—Kurdish refugees. In the last decade, thousands of migrants from Pakistan to West Africa have converged upon the Channel coast, with Calais and Dunkirk the largest encampments. They hope to cross to England, where they believe they have a better chance at refugee status. Each night, hundreds attempt to stow away on trucks, trains and ferries, but often meet death and detainment instead.

The migrants in the channel camps have all made a calculated but costly decision. Since migrants can only apply for asylum in the first EU member state they set foot in, and since they strongly prefer the UK for its perceived generosity, they avoid contact with the French state. Some burn their fingertips so they cannot be registered by French officials. Their hope for Britain means rejecting French government migrant centres and taking to the camps.

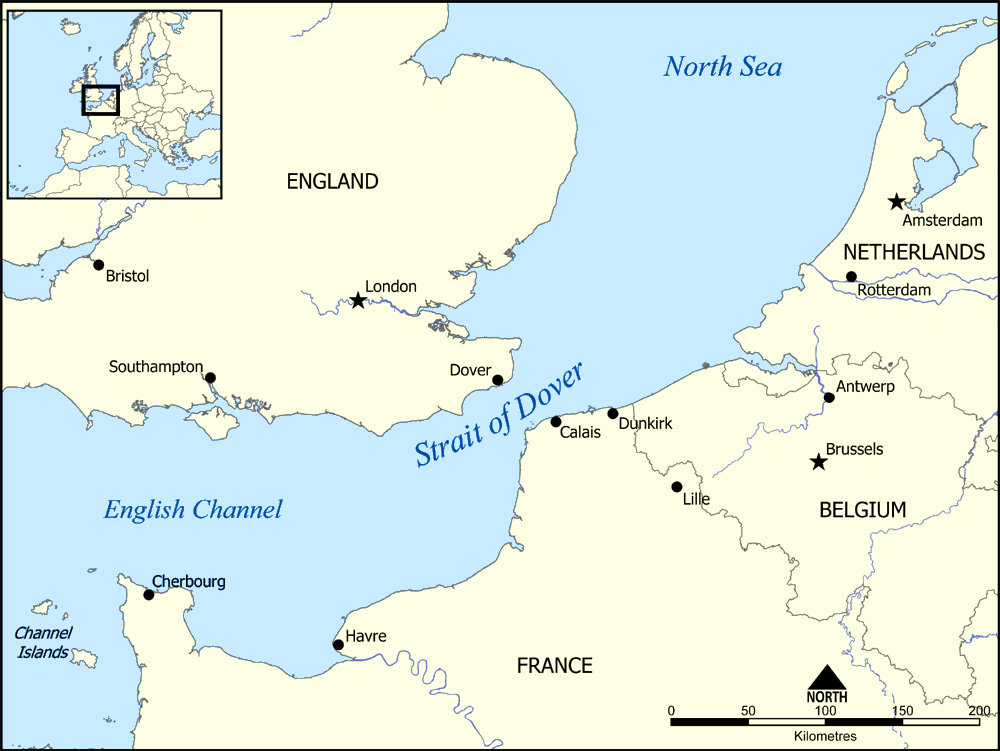

In late March, I travelled to the camp just outside of Dunkirk. Reading about the channel encampments, I imagined migrants gathered on the beaches, gazing bitterly at the English shore. In fact, the seaside cities bustle as before, with the camps on the inland outskirts, close to the railroads and highways that offer a chance of escape.

The settlement at Dunkirk began as a squatter colony around 2006, hidden behind a big box gardening store in the suburb of Grande-Synthe. Hundreds of Kurds, a stateless ethnic group spread across the northern Middle East, arrived each year, fleeing the ongoing violence in Iraq and the reprisals of regional governments against their independence movement.

The North Atlantic weather battered the site from the start, and photos show a settlement built not so much on the mud as in it. Only a trickle reached the UK, but growing conflict in Syria and Iraq swelled the camp. When ISIS swept across parts of the two countries, it pushed out thousands of refugees each month.

With new arrivals pouring in—increasingly women and children—the camp reached a breaking point this winter. It was a pit of unending cold, mud and disease, with nearly one thousand people sharing a single source of clean water and extremely rudimentary toilets. Dunkirk may not have inspired the same political or ethnic tensions as the Calais Jungle, but stood out for the sheer physical misery of daily life.

In response, the Green Party mayor of Grande-Synthe asked Médécins Sans Frontières to establish a purpose-built camp on the edge of town, with migrants arriving in early March. Along with a host of religious, humanitarian and leftist organizations, the mayor was directly disobeying the national government, which tried to shut the camp down down because its cabins were not up to building code. That newfound concern for the migrants’ safety met with ridicule, and government has since taken a less combative stance.

Housing about 2,500 souls, the new camp looks like a cross between a tent city and a construction site. It sits on an old industrial park, with lingering warehouses and an open lot set against a highway embankment. Under the whirring transport trucks, the town installed a drainage system covered by coarse white gravel. The migrants fly the Kurdistan flag and cover the cabins with Kurdish independence slogans that combine with the pale rocky ground to let you forget you’re in northern France. There is an impressive supply of mobile showers and squat toilet facilities, all impeccably clean thanks to municipal workers. There is plenty of food, if not much variety. Indeed, I personally helped throw out overripe bananas and bags of uneaten crusts.

I signed up to volunteer with Utopia 56, a youthful collective, receiving a blue identity armband and instructions to help haul garbage to municipal dumpsters. The nucleus of the volunteer corps is an unlikely mix: piercing-eyed, chain-smoking bohemians, redoubtable church ladies in work boots, and Farsi- or Arabic-speaking interpreters (the next best things to Kurdish). They direct a range of casual volunteers, mostly young and enthralled by their sense of common purpose.

Still, there is unease. The day before I arrived, a busload of industrious Germans flooded the camp with hard work and good intentions, then left after a few hours. The come and go of casual well-wishers like me is wearing on the permanent volunteers. I cringe as they complain that so few are willing to stay for a week, or even for the night shift, knowing I won’t likely be back myself.

The atmosphere here is nothing like the media’s image of Calais, with stern and filthy young men shivering around garbage fires. There is no rock throwing or hunger strikes in Dunkirk, and nothing like the walls of razor wire I saw from the train at Calais. Conditions are much better, and there is positive momentum as the camp improves. I presume the ethnic homogeneity lessens the tension, providing a sense of a shared fate among the residents.

Unlike Calais, migrants are free to leave the camp on foot or on old, ill-fitting bikes. The young men (still the majority) are mainly courteous and endearing as they proffer joking “hellos” and “bonjours” to volunteers and townspeople. The Kurds largely keep order among themselves, and when two of them tried to follow a young female volunteer home, it was another pair of migrants that stopped them.

The Kurds here are mainly rural in origin, and often illiterate in their own dialects, making communication difficult. Still, the young men clearly aspire to join the West’s popular culture. There is a makeshift barber shop churning out brush-cut hairdos, and their ill-fitting clothes and shoes are often imitations of European brands. They are not outwardly pious Muslims—I didn’t see anyone stop for daily prayers, there were beer bottles strewn outside the camp, and many women had uncovered heads. Their chief identification is with the Kurdish people, but their preoccupation is survival.

With the garbage disposal complete, I joined a young woman to act as a crossing guard on the highway, stopping traffic so the migrants could leave the camp. Most were buying bulk bread, candy and soft drinks for their little in-camp shops. But a steady stream of young men set out on the highway to Calais with small sleeping bags and a nervous grins. The church ladies wished them good luck, but never said for what. At least some of them make it to England—two weeks after I left, a Kurdish teenager named Mohammed Hussain was killed while clinging to the underside of a truck in Oxfordshire.

Like Hussain, many of the residents have family in the UK, and the Kurds are frank about their preference for England, its language, social services and perceived openness. And even though it’s the UK that doesn’t want them, France must enforce that rejection, reinforcing the Kurds’ view of the two countries. Indeed, efforts to start a school for the migrant children fizzled out over the question of language—the volunteers wanted to teach in French, the language of the migrants’ reality, but the parents insisted on English, the language of their aspirations.

With the muddy winter over, the migrants can look beyond the daily fight for survival. Their faces show relief, but also a new anxiety. A sense of permanence is setting in. The rows of cabins and clean toilets offer some comfort, but also signify that the Kurds will not be going anywhere soon. The mobile young migrants who started the camp in 2006 had some hope of making the secret journey to England, but most families here now will only reach the UK with official permission. There is no sign that British policy will change, even though many of the Kurds have strong cases as ISIS refugees.

As conditions came to a bitter tipping point this winter, the French refugee camps rose to international headlines. The armed dismantling of Calais and frozen hell of Dunkirk made for vivid reporting, but the camps have already receded from view. These migrant populations have existed for more than a decade now, and no victory over ISIS or new EU accord will truly stop the flow. The camps are a small part of the vast migration between and within countries that is a hallmark of our time. These movements of peoples, like most of the Kurds in Dunkirk, are here to stay.