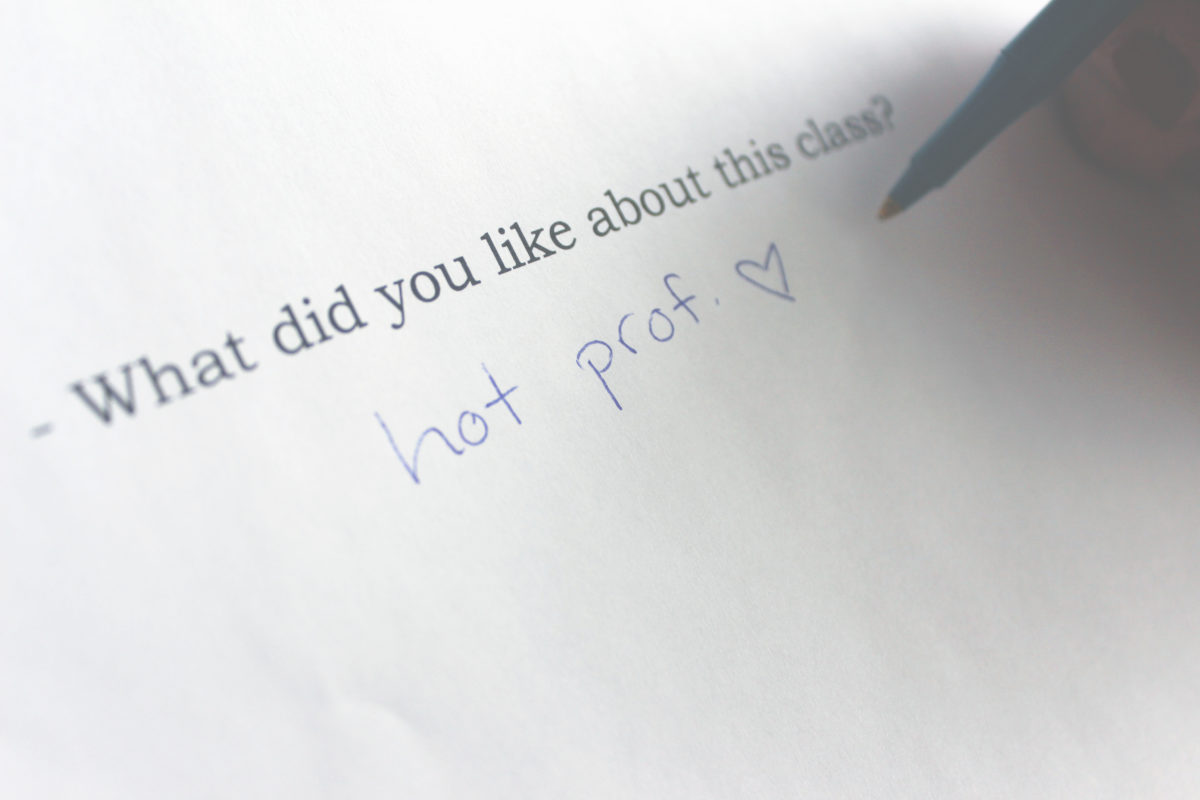

St. Thomas University criminology professor Karla O’Regan usually gets useful qualitative evaluations at the end of each semester. The assessments give students a chance to be open and honest about what they liked or disliked about a class, since they’re anonymous and only the professor sees them.

But sometimes, the comments have nothing to do with course material.

“Sometimes, you’ll get one that says ‘I’d get the professor laid,’” said the criminology professor. “And I had one that was terrible that said something about….bending me over a table. It was a very explicit sexual comment. And it was shocking.”

O’Regan believes these comments, while rare, are more common to women than to men. She doesn’t always get a sexually explicit review, but at least once per semester she gets one that focuses on her appearance rather than her performance as a professor. At the head of her own classroom, some students are more focused on the clothes she’s wearing than the words she’s saying.

“On one level, you can expect it, because that’s what we value women for: their physical attractiveness and it’s a bonus if you can also contribute intellectually to things,” said O’Regan. “It’s odd, though. I’m at the front of the class for a whole lot of reasons that have nothing to do with my appearance. Like five university degrees.”

Gender bias against women in academia is well-acknowledged, and it even comes from the students themselves. At a December 2014 study from the North Carolina State University, researchers evaluated a group of 43 students in an online course. The students were divided into four groups with one male and one female professor leading two each. However, the professors each told one of their groups their gender was opposite. The students gave higher scores at evaluations at the end of the course when they thought they were being taught by a man and lower scores to women. But the only change was the gender presented.

“Sometimes I do a kind of training with my students in advance of the evaluations,” said Kelly Bronson, a STU science and technology studies professor. “I have an open conversation: what kind of descriptions do you use for your male professors versus your female professors? I try to make visible for my students gender-laden descriptors.”

Bronson has not seen many comments she would describe as sexist. Her evaluations are great, but like O’Regan, students in her classes can sometimes cross the line, like calling her beautiful or saying they’re in love with her. She sees that most students intend to be complimentary, but she’s more interested on comments of the class than her looks.

“It’s a little bit of disappointment,” said Bronson. “I put a lot of work into prepping to teach and when a student doesn’t remark on that, I would like to know a bit more. I would like to have more productive comments.”

Earlier this month, a professor at Northeastern University gathered data on 14 million reviews from RateMyProfessor.com, a site for students to openly and anonymously say what they want about their profs and classes, and created an interactive chart to explore the words used for male and female professors. While appearance-based words like “sexy” or “hot” appear nearly equally for both genders, terms like “genius” or “good prof” are used significantly more often for men.

O’Regan used to search herself on RateMyProfessor.com when she was new to teaching and craved feedback. She didn’t realize the kinds of comments she would find there.

“It was all about how hot you are,” she said. “The very first year, I remember reading them and then crying.”

O’Regan doesn’t want to be sexy at work. It’s not a beauty pageant and she thinks students at a university should be better than that. But if a student in her class doesn’t like her, often her gender is the first target. Sexist comments are not the norm, but O’Regan says they’re representative of a wider societal problem of judging women based on sexual attractiveness.

“You start to feel sick and belittled and a bit embarrassed,” she said. “You remember how hard you worked for so long, and in the end it matters more what you look like.”