Content warning: Please be advised this article discusses residential schools and genocide.

This story is part one of a two-part series about Truth and Reconciliation Day. The next part will discuss the upcoming events happening for the holiday.

Logan Perley woke up on the morning of Sept. 1 to his phone buzzing. Everyone was talking about New Brunswick’s decision to not recognize Truth and Reconciliation Day as a provincial holiday.

“I remember when I first saw it, my stomach sank,” said Perley, the communications assistant at Wolostaqey Nation of New Brunswick.

He was disappointed but not surprised.

This August, Canada formally recognized September 30th as a national holiday. The province’s choice not to recognize the day means that federal employees will have the day off. But, it is up to personal institutions in New Brunswick if they want to close their doors.

Truth and Reconciliation Day, formerly called Orange Shirt Day, is an answer to one of the Truth and Reconciliation Commissions 94 Calls to Action that asked for “a federal recognition to honour Survivors, their families and communities and ensure public commemoration of the history and legacy of residential schools.” Perley saw the conservative government’s decision as them not holding up their side of the bargain.

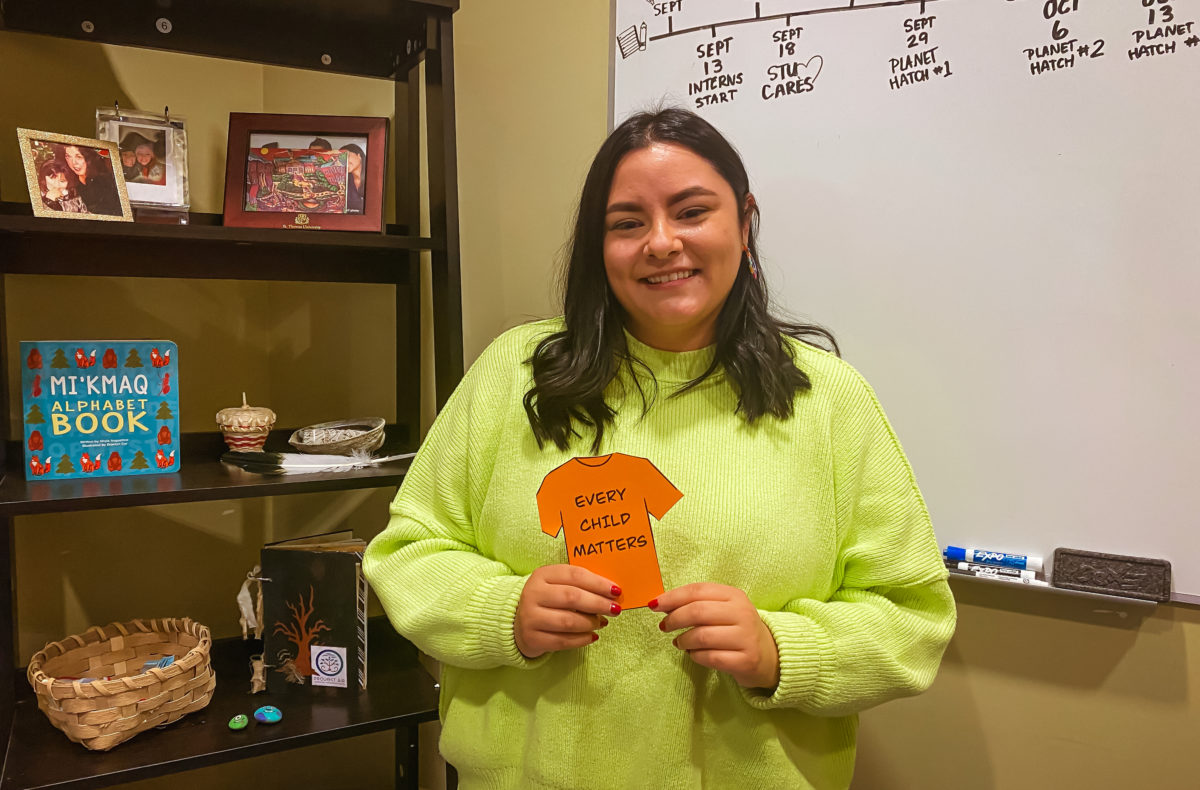

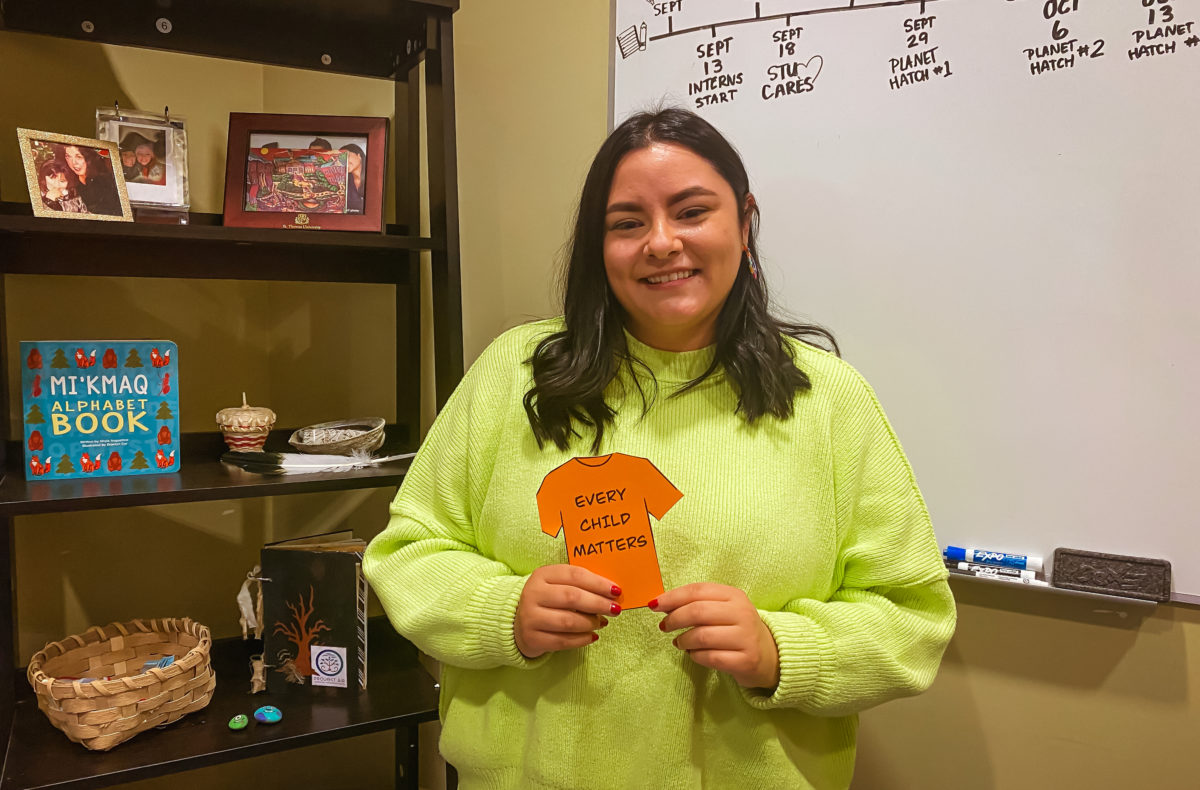

“It’s another way Indigenous people are going unsupported in New Brunswick,” said Rachel Burke, STU’s Indigenous experiential and community-based learning coordinator. “Just not having it at a government level shows there might not be as high of a dedication to reconciliation as one would want or expect.”

Leanne Hudson, a fourth-year STU student and student representative at STU’s Senate Committee on Reconciliation, called New Brunswick’s decision eye-opening.

“If the province isn’t recognizing it as a holiday or isn’t giving that space for people to learn or educate themselves or to heal, to reflect, then it really promotes this negative message that we don’t need that time,” said Hudson.

Despite the provincial decision, St. Thomas University has decided to close its campus and cancel classes on September 30. Burke sat in on a conversation with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission at STU when they were making the decision.

All agreed the school should close as a day of reflection. Burke said that when making the decision, their primary concern was how Indigenous Peoples inside and outside the university would feel.

Given STU’s high population of Indigenous students and the university’s commitment to Truth and Reconciliation, Burke said it makes sense for STU to close its doors.

“It’s just our responsibility to Fredericton, to New Brunswick, to all Indigenous people to close that day, so it’s for them,” said Burke.

In her role at STU, Burke works with other Indigenous staff members like Wendy Matthews and Trenton Augustine to make sure Indigenous students feel supported on campus. With the extra controversy around the holiday this year, she wants Indigenous students to know that STU and its faculty respect Orange Shirt Day.

As a STU graduate himself, Perley was happy to see the university give the day off for students to reflect.

“To Indigenous students, this will really be on the same level as Remembrance Day,” said Perley.

The recovery of 215 children’s remains from Kamloops residential school this summer prompted the search of sites across Canada and the United States.

Since then, 20 former residential schools have been searched and over 6,000 remains of children have been recovered. Perley said the discoveries show what Indigenous Peoples have known all along. He said it is important to remember that the experiences of residential schools aren’t a thing of the distant past.

“When you can remember something that happened to your mother or your father or grandfather, you are not going to forget it,” said Perley. “You are going to be upset when you feel like their pain is unnoticed by the government.”

The last residential school in Canada closed in 1996, making this year the 25th anniversary. Hudson asked why it took so long for the government to look into the unmarked gravesites and why it took 1,300 children to be discovered for the government to name it a national holiday.

“It’s Truth and Reconciliation Day, but do we even know what truth and reconciliation is?” asked Hudson.