It was the summer of ’77, a frail 74-year-old man by the name of Henry Cordle was murdered in his room at the YMCA in downtown Toledo, Ohio. He had suffered 37 wounds, three of them deep stabbing. There were no witnesses.

In September of that year, a young man named Michael Morris – who lived in the same building as Cordle and who had not returned since the day of the murder – was arrested. Most residents of the YMCA had been questioned by police. One of those inhabitants was Michael Ustaszewski. The police had told Morris that it was Ustaszewski who had mentioned his name. After, Morris said he was a part of the robbery which had also been committed in Cordle’s room, but stated that it was actually Ustaszewski who had done the killing.

Ustaszewski was arrested the next day.

Ustaszewski proclaimed his innocence, but he never refused to cooperate with police. He admitted he and Morris had contemplated committing robberies, but had said none of them ever happened. Both men were convicted of aggravated murder and sentenced to 15-years-to-life in prison.

Ustaszewski was 18-years-old.

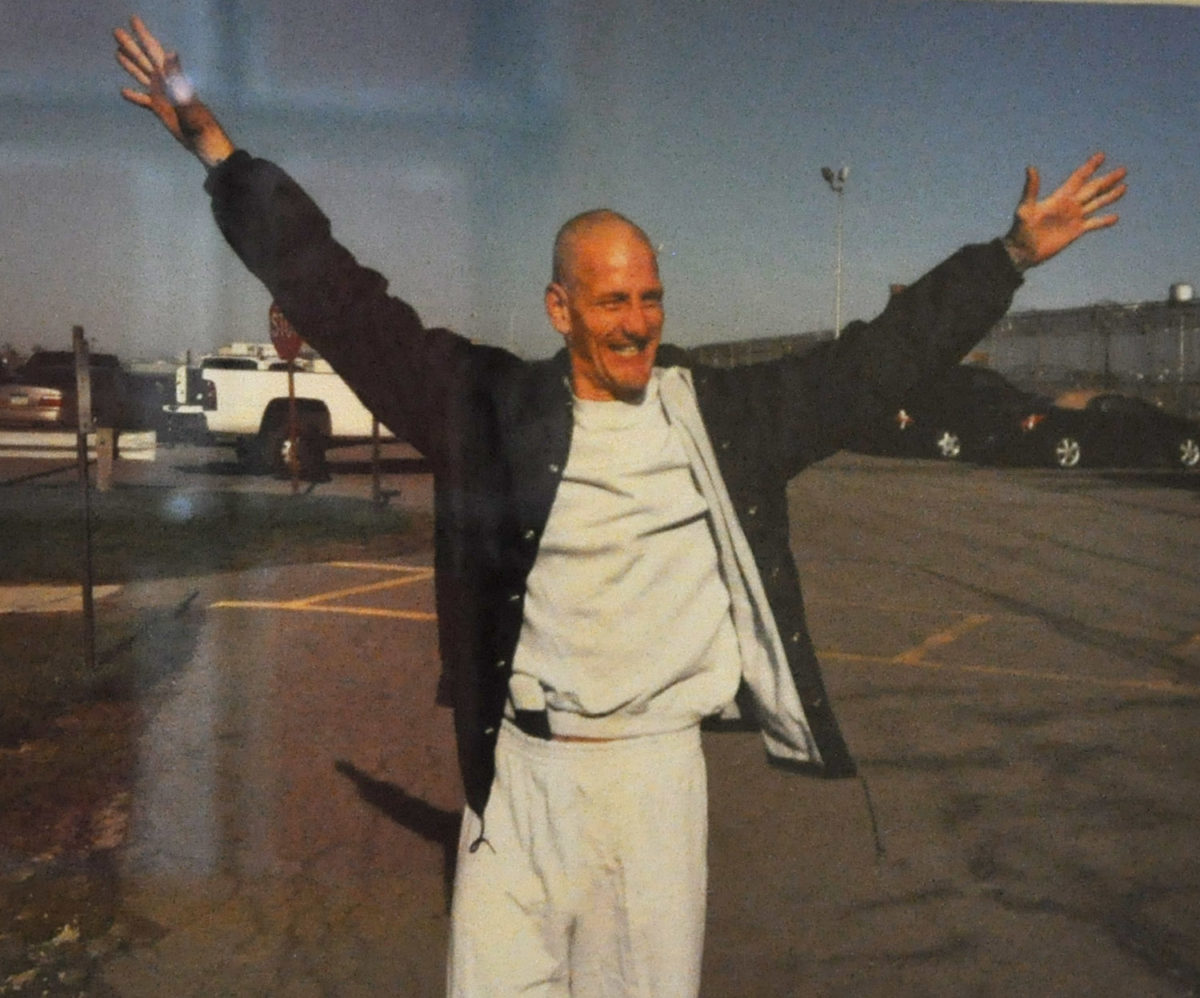

In April of last year, at almost 54-years-old, Ustaszewski was released on parole. After 35 years Ustaszewski still claims his innocence and will not feel free without exoneration.

“I went down to see him when he was released and I spent the first five days of his release with him, and decided that one thing that might be interesting would be to document his experiences,” said Melissa Sheridan Embser-Herbert, endowed chair in criminology at STU. “This was partly a way to keep people interested in his case, but also human interest generally.”

On a blank curved wall on the fourth floor of Brian Mulroney Hall are 12 photographs taken during the first week of Ustaszewski’s release. This exhibit is a part of Embser-Herbert’s project Journey Toward Truth, which documents through photo, video and text what it’s like to return to society after more than three decades.

“My family knew him back when he was a teenager, but I never got to meet him because I was already gone to university. My mom and I were driving from Minnesota to New Brunswick and we’d be going right through Ohio and I asked her if she wanted to stop and see him,” said Embser-Herbert. “I remember thinking, ‘Whoa, that guy is still in prison.’”

In 2009 Embser-Herbert first met Ustaszewski and began investigating his case.

“I spent six hours with this guy and left thinking he had been totally railroaded.”

Most of the exhibit’s photos capture the every-day and mundane things, like marveling at a travel mug in Target to wolfing down a foot-long sub and catching up with family. But for Ustaszewski, this was a changed world.

“He describes it as going to prison during the Flintstones and coming out the Jetsons, but I think he’s doing remarkably well for someone who went in so young and never lived as an adult in the real world,” said Embser-Herbert.

Embser-Herbert recalls Ustaszewski’s first day out of prison. They had gone to a restaurant for supper and Ustaszewski found himself in the weird world of motion-sensored bathrooms. He started freaking out because he didn’t know how to flush then he searched for the sink’s tap, but to no luck.

“You could tell he was thrilled to be released, but there was just so much sensory overload,” she said. “That’s something that I could never begin to capture through photos. That’s something only he can understand.”

The personal images were first displayed at Hamline University in Minnesota, Embser-Herbert’s home institution, which partially funds Journey Toward Truth. Embser-Herbert was encouraged to display the photos at STU by criminology professor Chris McCormick, who has a strong interest in visual criminology.

“The stories and the visuals make visible a life which was hidden from public view, a life which was arrested in the course of life events which all would otherwise experience and enjoy. The fact that deaths, births, relationships and life would be interrupted by a wrongful conviction is important to document, in this case by photographs and stories,” said McCormick.

Ustaszewski is still working with Embser-Herbert to get his story to people all over the place. He is hoping one day he’ll be able to go back into the prisons and work with youths.

“These are all ways of getting his story out there and hopefully making a difference,” said Embser-Herbert.

The exhibit will be on display until the end of April.