A video created by an entertainment news site and YouTube channel Collider shows Robert Downey Jr., Tom Cruise, George Lucas, Ewan McGregor and Jeff Goldblum at a round table where they discuss the streaming wars between Netflix, Disney+, Hulu and cinema.

When asked about seeing Star Wars in theatres, Downey Jr. said, “It’s one of those things where you remember where you were at the time. I remember because I was peeing my pants because I was a child.”

But Downey Jr. isn’t actually saying those words.

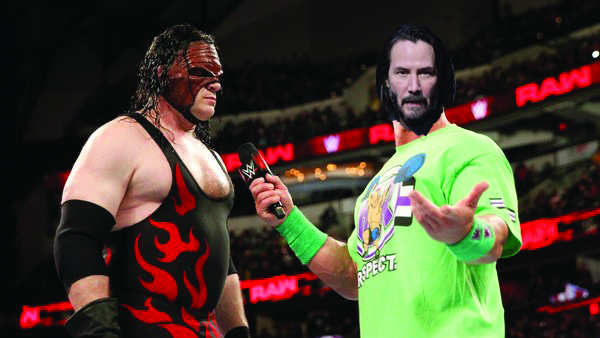

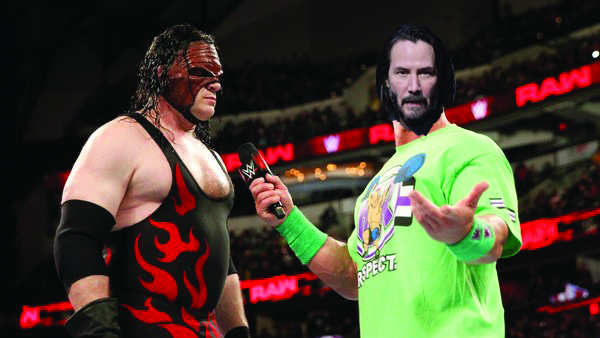

The catch is, they’re not actually the A-listers. Collider used deepfake technology to make their actors look and sound like these stars.

Deepfakes are a type of media that take a video or image and replaces the existing image of a person with an image of someone else. In videos, deepfakes also replace the actor’s voice with the person they’re imitating. If the person gives a convincing performance, we’re led to believe they can actually be someone else, such as Robert Downey Jr.

James Dean died in 1955, yet he’s set to play in a supporting role in Finding Jack, a Vietnam War film. This is done by using samples of Dean’s image and voice, which deepfake technology uses to bring the actor back to life.

Duncan Philpot, PhD candidate of sociology at the University of New Brunswick, said this move raises some philosophical and ethical questions.

“It raises questions about identity and what happens to our self after we die,” he said.

“What impact will these have with regard to cultural memory and memorialization of the individual?”

Deepfake technology allowed Snoop Dog to perform with Tupac Shakur at the 2012 Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival. It also allowed Michael Jackson to perform at the 2014 Billboard Music Award five years after his death.

But it’s more than the big production companies who have access to deepfake technology.

Peter Weeks, a sociology professor at St. Thomas University, said FakeApp 2.2. allows everyday people to create photorealistic face-swap videos. While users can use it as a form of entertainment, it can also be used to promote political propaganda and disinformation.

“Politicians are photographed a lot, often standing in a fixed position,” Weeks said.

“This makes them incredibly easy subjects for deepfakes.”

Weeks said deepfakes will require Canadians to become better at criticizing and analyzing what they see online since this technology adds to the “fake content” problem.

Last year, director Jordan Peele and the chief executive officer of Buzzfeed released a video of Barack Obama where he calls President Donald Trump a “total and complete dipshit.” They used FakeApp and Adobe After Effects to create the video.

In May, another deepfake video showed Democratic House Speaker Nancy Pelosi slurring her speech to make her appear drunk.

But like any technological tool, Philpot said deepfakes aren’t inherently bad. It’s the way people use it.

“At present, their utility is being experimented with and those of us who have seen how they can be applied have likely seen both its use for entertainment as well as political purposes.”