A climate emergency teach-in last week highlighted the need for sustainable and ethical environmental practices in New Brunswick. St. Thomas University students from professor Matthew Hayes’ sociology class organized the talk using the tagline, “this is not a drill.”

“This is not hypothetical,” said University of New Brunswick environmental law and policy professor Jason McLean, a speaker at the teach-in. “This is not a theoretical academic topic, we are really in a decade of make or break action for the climate and for human systems.”

Joining McLean Wednesday night on Zoom was STU professor Tracy Glynn.

McLean opened the talk with a global view of the climate crisis. He walked the audience through recent reports that contextualized the time humanity has to turn global emission trajectories around.

How much global greenhouse gas emissions is left?

McLean began his talk by introducing the remaining carbon budget, which is associated with limiting warming to 1.5 C. McLean said that any warming above 1.5 C will bring disruptive impacts like more intense forest fires, storms, malnutrition and biodiversity loss.

“Every fraction of a degree of warming brings with it increasingly disruptive impacts to human and natural systems that have a really high cost,” said McLean.

Using the precautionary principle, the planet has warmed 1.3 C, which means it only has .2 C left before hitting the 1.5 mark. This principle advises caution, which is recommended by environmental scientists.

For a 50 per cent chance of staying below 1.5, the world has 500 gigatons of greenhouse gas emissions left. For a 66 per cent chance, it has 400 gigatons. For an 83 per cent chance, it has 300 gigatons. To put that in perspective, he said in 2019 alone, humans produced 59.1 gigatons.

“That gives us fewer than ten years to level out our trajectory and to be on a path to net-zero by 2050,” said McLean.

He said people need to change how energy is generated and the agricultural systems at use, a neglected but important contributor to global warming.

COP26

This talk purposely coincided with COP26, a climate change conference for the United Nations. Environmental activist Greta Thunberg recently called the event a failure and PR stunt in a speech outside the conference.

McLean said to expect big promises being made by political figures, some of which were made in the past but lacked follow through.

He said Fredericton is developing as if there isn’t a finite global carbon budget, building infrastructure that is meant to last 40 years but will be unsustainable in five.

“We need to be able to understand nationally, internationally, regionally, locally, in our own municipalities what we’re doing in terms of implementations,” said McLean.

A just energy transition in New Brunswick

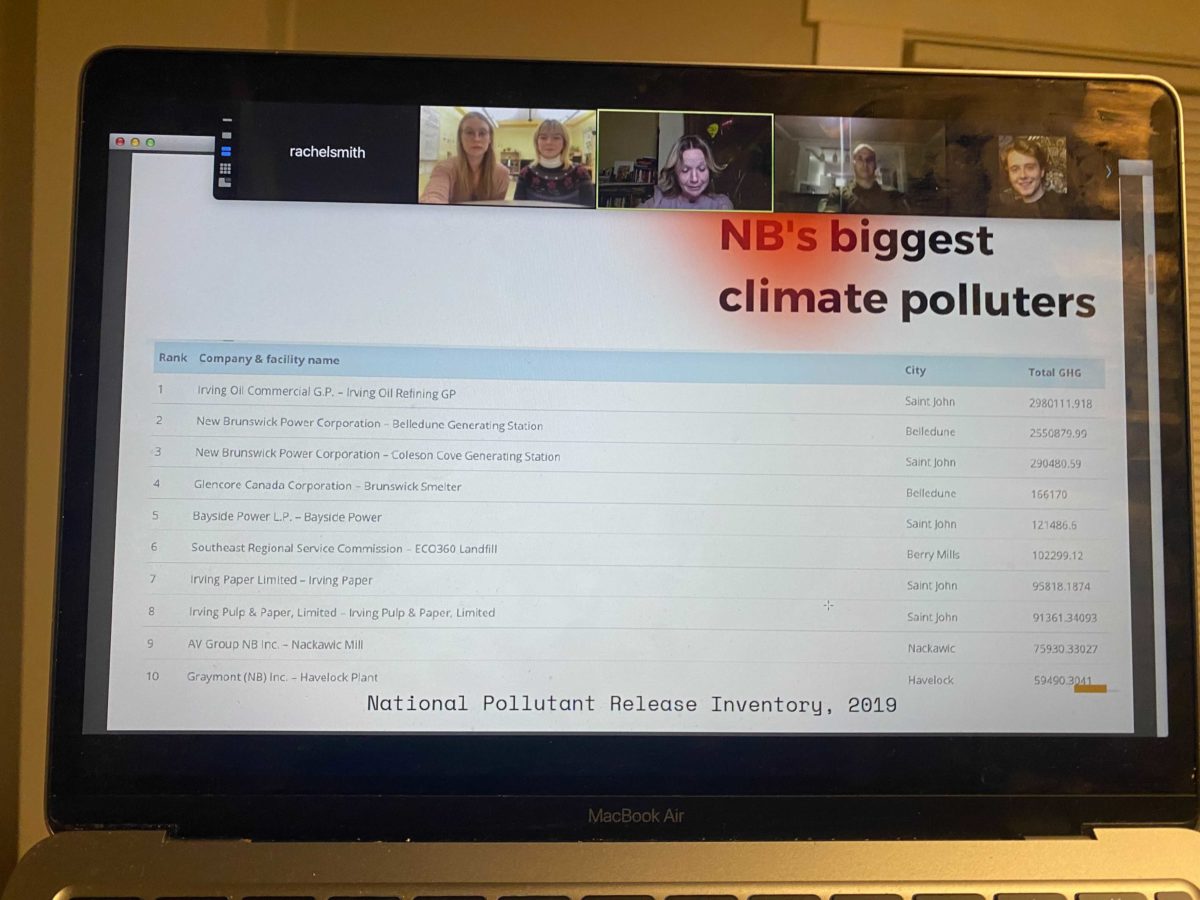

Tracy Glynn, who teaches environment and society programs at STU, started her presentation with a list of the top climate culprits in New Brunswick of 2019. She added a regional context for those living in N.B.

Glynn said that many environmental activists and scholars name capitalism as the root of environmental problems.

The nature of capitalism degrades ecosystems and when degraded, moves to another place. She said that sometimes potential environmental solutions create anti-environmentalists.

“People don’t want to identify with the environmental movement because they see racism and classism in population growth control strategies and carbon offset schemes that keep the carbon in the ground in one place only to destroy the forests of Indigenous Peoples somewhere else,” said Glynn.

She said capitalism is good at hiding the social relations behind how goods and services are produced.

For example, N.B. Power burns coal mainly extracted from two mines in Columbia owned by Glencore.

Colombian coal is called black coal because of the assassinations of union leaders, some at the coal mines. Glynn said that in order to get coal underground, communities are violently displaced.

“The Indigenous Wayuu and Afro-Columbian Peoples live in poverty and with no drinking water, a result of a diverted river for the mine,” said Glynn. “They suffer health conditions from living next door to one of the world’s largest open-pit coal mines.”

Activists in New Brunswick responded by working in solidarity with leaders in Columbia affected by mining. Since then, recent reports from the Cerrejón coal mine show that the mine has expanded.

The presentations were followed with a question-and-answer portion from the audience, where the question of electric cars and SMRs was posed. Both speakers challenged these potential solutions for the climate crisis, McLean said there are no “silver bullet solutions.”

When convincing those in power to implement change, McLean suggested arguing scientific-backed statistics then follow with ethical reasoning.

“These ‘business as usual’ trajectories are imprudent financial investments and unsustainable,” said McLean.

He said that perpetual economic growth is not conducive to a planet with finite resources. McLean said it’s important for individuals to involve themselves with politics in order to make a change.

What to do as students?

Tabitha Evans, a third-year sociology major with a focus on environmental policy, was one of the main student organizers of the event. She called it a collaborative effort between classmates, springing from the realization that the students didn’t know as much as they wanted about climate change.

Evans said she was pleased with the turnout and subjects highlighted by McLean and Glynn.

“I found [the speakers] really engaging,” said Evans. “They did a really great job of relating the climate crisis back to stuff as students we can relate to and also in a geographical context.”

She thinks the next step is for students at STU to initiate structural changes within the university.