The establishment of a free Ukrainian state is more complicated than the Western world acknowledges, Mikhail Molchanov told an audience of political science students Tuesday.

“The main issue is the Cold War mentality which unfortunately existed in the West through this last 25 years. Despite assurances to the contrary, Russia was never taken seriously as a partner, even when the government was much more democratic than it is now,” the St. Thomas political science professor said after his lecture at the Noël A. Kinsella Auditorium.

Molchanov said he isn’t trying to advocate for Russian separatists or for an independent Ukrainian state; he’s trying to add shades to this black-and-white media portrait. But he argued Western nations and media should acknowledge that the Russian-speaking rebels have legitimate grievances and aspirations.

“All these movements and these people are being presented as Moscow puppets — which is not true.”

Elections on Oct. 27 left Ukrainian parliamentary power firmly in the hands of pro-western parties. Millions of Russian-speakers in the south and eastern part of the country did not participate. Instead, they held elections Sunday – elections not recognized by the Ukrainian government or the West although sanctioned by Russia.

In a country of 44 million, six million people from the eastern half of the country are excluded from the political process, said the Ukrainian-born, Russian-speaking professor.

“[The] Russian community in the South has separate cultural interests, which are not currently served by the Ukrainian government,” Molchanov said. “However, it doesn’t mean separation is the only option. If the current government actually starts taking into account those cultural interests, this problem can be resolved.”

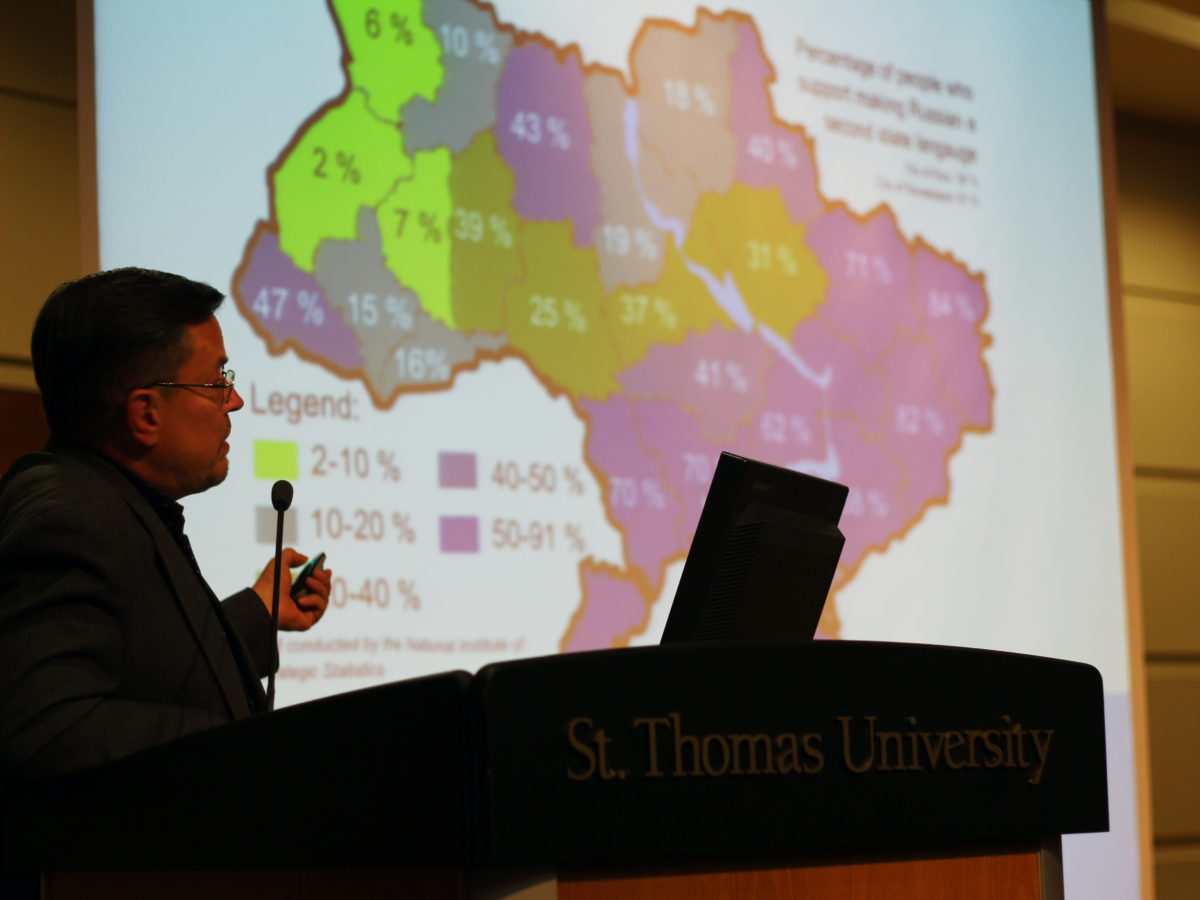

According to Molchanov, these cultural interests include the official status of the Russian language (while more than 40 per cent of Ukrainians speak Russian as their language of choice, Ukrainian is the only official language), education for Russian-Ukrainian children and Russian cultural rights.

Although a more representative Ukraine is possible, the civil war is making it difficult, he said.

Starting in March, Russian-backed rebels seized government buildings in the East and South of Ukraine. An estimated 2,500 have died in fighting since. Russia has sent military equipment and troops in what some have described as a stealth invasion. Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 was shot down in July, killing approximately 300, with what many believe was a Russian missile launcher.

While an official ceasefire has been in place since August, sporadic fighting between rebel militias and Ukrainian forces continues.

Molchanov said this Russian southern separation isn’t the only issue when it comes establishing a free Ukrainian state. With the January removal of Russian-backed president Viktor Yanukovych for the more West-oriented Petro Poroshenko, Ukrainians thought they were moving towards a corruption-free government. But Molchanov isn’t so sure.

“The whole point of the [Euromaidan] revolution was precisely to use Ukraine’s associate membership in the E.U. to fight corruption at home,” Molchanov said. “That is why the Ukrainian population was so enthusiastic about this. They felt so exhausted in their own fight against the corrupt government. They thought, ‘Maybe if we move closer to the E.U., maybe European bureaucrats and European politicians will help us clean up the government.’”