What, in geographical terms, fosters talent, creativity and the arts? Not provinces or nations, but cities.

To use author and professor Richard Florida’s term, the creative class live in cities— in fact, they thrive there. But not any city; Florida insists it is the quality of place— a place of diversity— that creative-minded people enjoy.

Halifax has plenty of potential in this regard. Florida himself points to Halifax, with more than 70,000 people employed in creative sectors, as poised to be a creative economy leader.

In 2012 Florida told the Chronicle Herald, “Halifax has made great strides in improving its quality of place. I believe we are really seeing the community bloom into a vibrant creative centre.”

Those who make up the creative class are scientists, engineers, poets, architects and writers— anyone who creates new ideas, technology or creative content.

These people, living in close quarters and exchanging ideas, stimulate innovation, not politicians who enjoy using the word for its political capital.

So where do the largely homogenous cities of New Brunswick— Saint John, Moncton and Fredericton— fall in the realm of creative economies? Somewhere between paint-less paintbrush and a blank canvas.

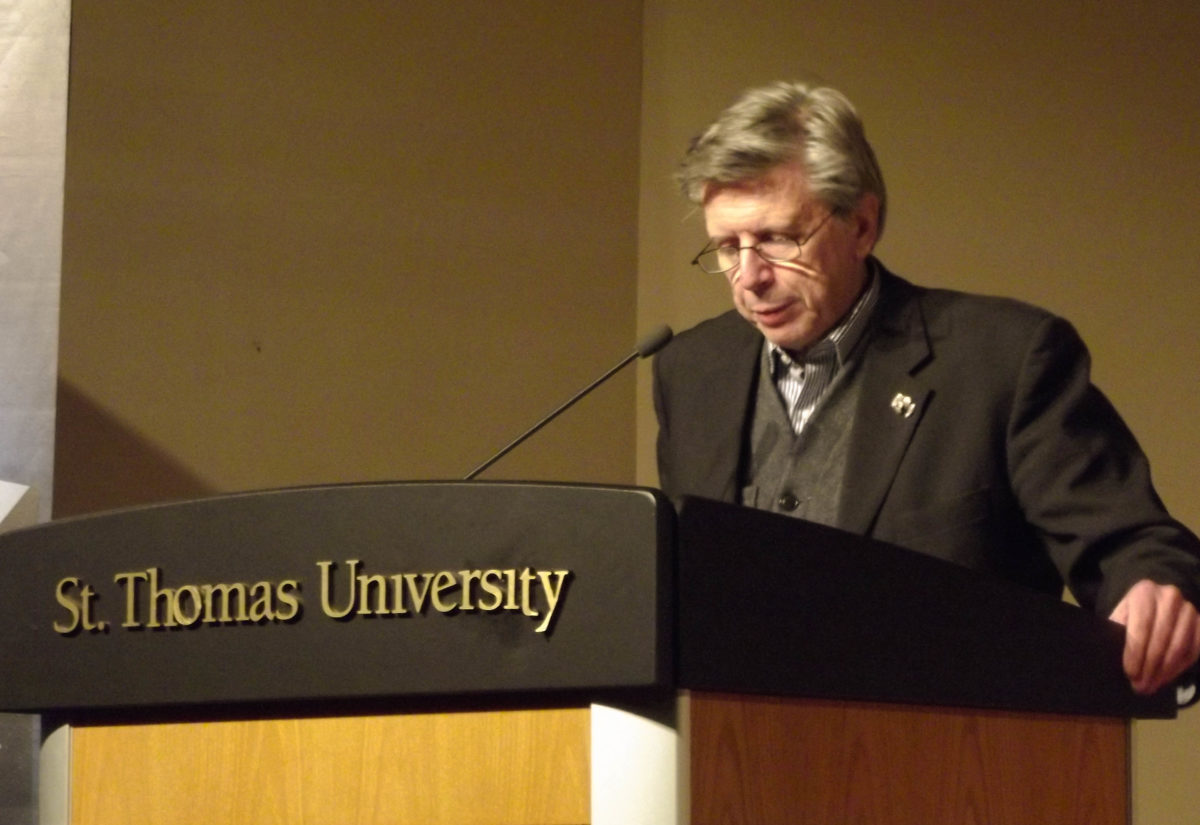

Herménégilde Chiasson, former Lieutenant Governor who now teaches at the Université de Moncton, spoke earlier this month at the STU Kinsella Auditorium on the potential of a knowledge-based creative economy in New Brunswick.

“We live in an age where we have to draw connections in order to increase our efficiency. The linkage of the arts falls in that prerogative,” said Chiasson.

In a province steadily falling into economic decline, it is clear, with recent provincial cuts to physical education and music, the Alward government’s priorities lie elsewhere.

Chiasson fears that in New Brunswick, if something can’t be quantified, it will be abandoned.

“Statistics related to the arts are always subject to a form of discrimination for we do not seem to fit in the world of numbers. The result is that the arts are still not seen as an industry that contribute to the growth of the economy,” Chiasson said.

So, what makes the arts community in Halifax different from Fredericton? We live in a global market that prefers economies of scale, which allows larger cities to not only produce more, but diversify the goods, services and ultimately cultural institutions it produces.

Take Calgary for example, a city born out of the 20th century— not exactly historic. So what is culture without history and heritage?

Saint John, as Canada’s first city, has hundreds of years worth of history and heritage. But with only 130,000 people, it doesn’t have the critical mass for a creative hub.

Culture can take the form of creativity. Calgary is a place people flock to, which means that while it may lack cultural heritage, it makes up for it by spurring creativity.

Diversity is the key word here. Yet, we have three cities with three distinct roles. Saint John has the port and heavy industry, Moncton with retail and distribution and Fredericton as our seat of government and a fledgling tech industry.

Dividing our already small urban population by three cities just won’t create a thriving arts community.

It’s an uphill battle; it will take more than buzzwords and rhetoric to bring a knowledge-based economy to New Brunswick. Like everything, an overhaul of antiquated public policy is required.

Step one: electing innovators to public office.