I was born and raised in a little place called Clark’s Corner. It’s 20 minutes outside of Minto, but it’s what everybody else calls “the middle of butt-fuck nowhere.” My house is in the woods, and it’s the most peaceful, serene piece of paradise in the entire world as far as I’m concerned.

But I went to school in Minto, I hang out with my best friends in Minto, I’ve gotten myself in trouble in Minto, and as of late, I even represent Minto. You can call me Miss Minto, or Miss “Minno” as we Mintonians say.

Minto has a reputation for being a badass village whose foundation has been built on drugs, hockey and welfare cheques. I’d be lying if I said that’s not a little bit true. Minto is the place where teenagers with no future come to either fight or get wasted, adults come to live cheaply, and the elderly stay because they never got the chance to leave. You’re either hopelessly in love with it, or constantly hate it.

***

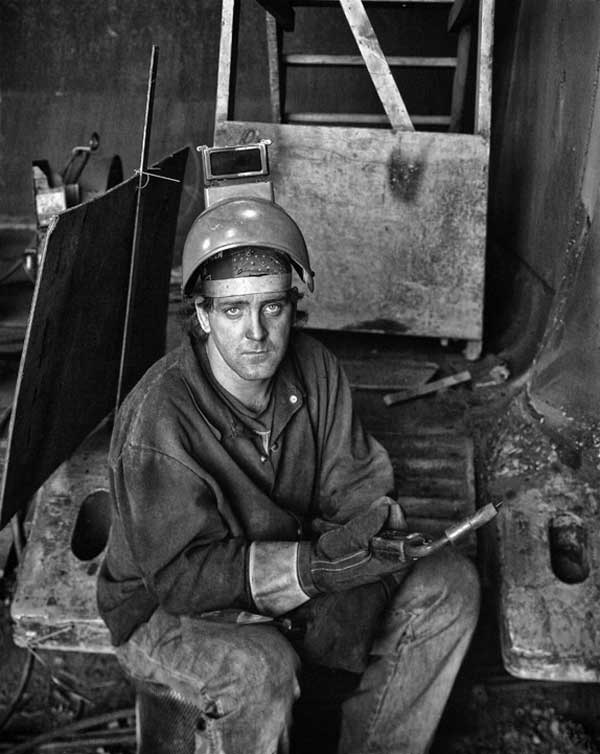

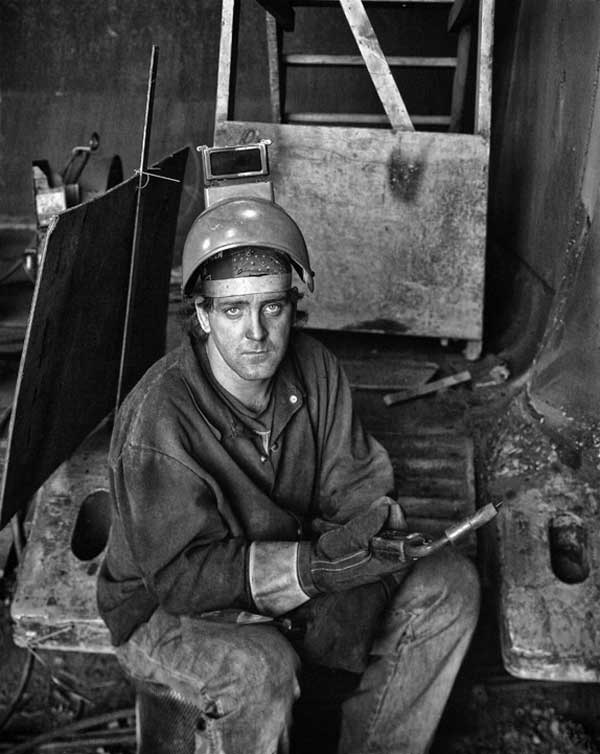

I grew up seeing Minto romantically. Hard-working, tobacco-chewing, dirty men would slave in the coal mines for hours upon hours each day. In pictures I’ve seen, these men were hardened – real Clint Eastwood types with the boyish faces of Paul Newman; the types forced to quit school in elementary and work to support their ailing families before they hardly even knew what money was.

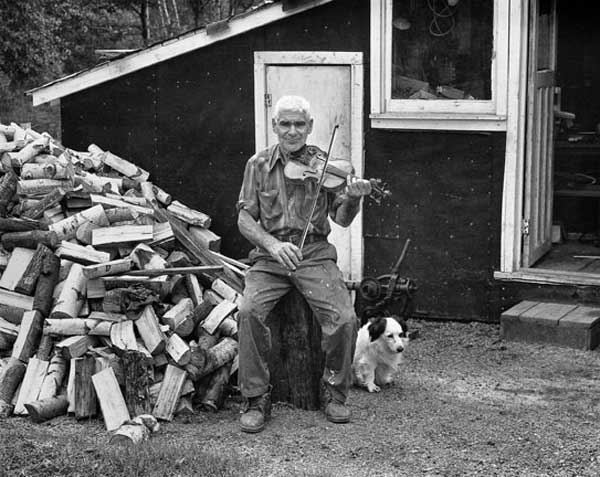

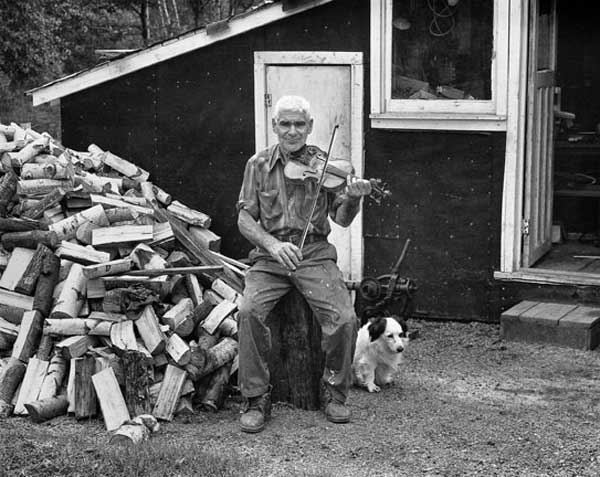

A busy Main Street would have all classes of people tipping their fedora and panama-style hats to each other or shaking calloused hands. It was lined with little family-run businesses in those days, and not a building was abandoned – there’d be a patriarch pulling out his wallet faster than a cheetah can run.

By the time the last coal mining company in the area, NB Coal, closed in 2010, the entire community had become like a person on death row, hoping his sentence would be commuted. After more than 370 years of coal mining in Minto, hundreds of people lost their jobs. For a village of 2,500 people, the loss was devastating, both economically and emotionally.

When you first get into the village limits, next to the dark green sign with yellow letters that welcomes you to Minto, you’ll notice a bucket from one of the old draglines – a reminder of what the village used to be. There’s a small building on Main Street that used to be a train station – the hub of the community at one time – and it’s now a museum. Inside are photographs of old trains and the miners hard at work, and there is an entire room dedicated the old miners and their stories.

Everywhere you go around the community there are reminders of what Minto used to be, but hardly anything that points to its reinvention as a village. Buildings have been abandoned and left to dilapidate, businesses are slim (one of our two grocery stores just closed, and there’s only one gas station), and young people are on either on the street or hate their lives – looking for something better than what they’ve been dealt. Their parents have to travel anywhere between an hour and 5,000 kilometers away to provide for them, and their grandparents are made sick because of it.

But I don’t see any of that. When I look at Minto, I see a place that lost its crutch and kept going. I see people lending a hand to those who need it the most. I watch families helping other families raise their kids when times get tough. I hear “Hello!” and “How ya doin’?” between each aisle of the grocery store no matter how well the voices know each other. I feel the energy and vibrations of laughter as people bond over a jam session, a hockey game or a coffee. I witness people make the most of what they have although it’s often so little. I watch people stay, not because they’re confined to this life, but because they believe in it. I stand in the middle of a community that never stops being one.

My grad class voted a country song by Montgomery Gentry as our grad song. It was the first line that did it for us: “Don’t you dare go runnin’ down my little town where I grew up, and I won’t cuss your city lights.”

When people hear I’m from Minto, they either ask me where it is, or say how bad they’ve heard it is. It takes everything in me not to explode. But I think that song says it all. You can’t really know how great a place like Minto is until you experience it. You have to be in the middle of a Saturday night hockey game sing-a-long, or tag along with your parents to a kitchen party. You have to watch the boats come into the coves of Grand Lake at sunset on Labor Day weekend and listen to the whoops and hollers of people in a place that doesn’t even qualify as a town. You have to see everybody’s lives unfold as one. Only then will you understand how profound Minto, New Brunswick is.

I always get asked how scary coming to university was since I’m from such a small place. What I’ve realized in my first semester is that it’s my hometown roots that keep me grounded when things get overwhelming; no matter what, I can always go home to open arms and good music. In this crowd of new faces and nameless people, Minto is my little secret.